The Consultative Committee has presented to President Rodrigo R. Duterte the Draft Federal Constitution. Below are some comments that may be made in respect of the provision on National Territory contained in the draft that has been released online.

ARTICLE I NATIONAL TERRITORY

SECTION 1

The Philippines has sovereignty over its territory, consisting of the islands and waters encompassed by its archipelagic baselines, its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, and its airspace. It has sovereignty over islands and features outside its archipelagic baselines pursuant to the laws of the Federal Republic, the law of nations, and the judgments of competent international courts or tribunals. It likewise has sovereignty over other territories belonging to the Philippines by historic right or legal title.

SECTION 2

The Philippines has sovereign rights over that maritime expanse beyond its territorial sea to the extent reserved to it by international law, as well as over its extended continental shelf, including the Philippine Rise. Its citizens shall enjoy the right to all resources within these areas.

The Philippines has sovereignty over its territory – The formulation provides emphasis, but likewise reveals the circular statement of the concepts of sovereignty and territory as elements of statehood. As we know, in addition to people and government, a defined territory and sovereignty over such territory are the elements that compose a state. Thus, having ‘sovereignty over its territory’ seems to say little insofar as stating the extent of national territory; the phrase operates to describe the nature of the right of the state which is essentially a given. In any case, this sentence is supplemented by the clause ‘consisting of the islands and waters […].’ Thus, the extent of such territory is defined by making the archipelagic baselines the point(s) of reference.

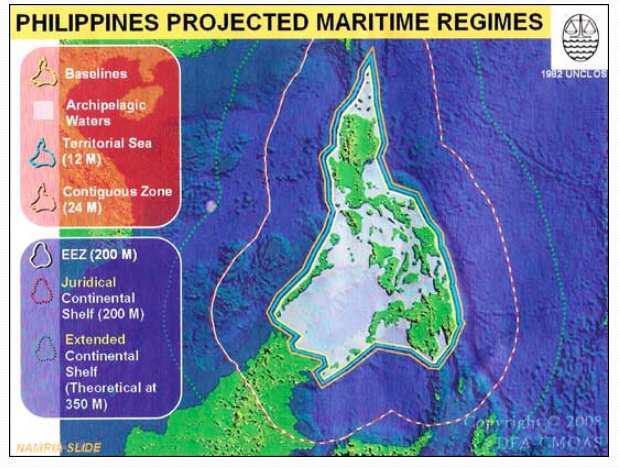

Concerning the mention of the territorial sea, that it is part of a state’s territory is a rule firmly established in international law; the seabed of the territorial sea, as well as the subsoil of the land features, and the superjacent airspace, are considered part of a state’s territory. (When and where the Philippines shall define the extent of its territorial sea, which is limited only to 12nm, remains to be seen.) The problem, however, is the inclusion of the territorial sea in this sentence as though it were within the archipelagic baselines. Such an idea is factually incorrect and legally insupportable given that the territorial sea of an archipelagic state is measured from the archipelagic baselines seaward following the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC).

It appears sound that archipelagic baselines are made the reference point in defining the national territory. The waters encompassed by said baselines are thus deemed archipelagic waters through which foreign vessels enjoy not only the right of innocent passage in the territorial sea, but also the more controversial right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. Within the archipelagic baselines are archipelagic waters, without the archipelagic baselines up to a maximum distance of 12nm therefrom is the territorial sea.

It has sovereignty over islands and features outside its archipelagic baselines pursuant to the laws of the Federal Republic, the law of nations, and the judgments of competent international courts or tribunals.

It can be asked whether the sentence describes (a) the extent of national territory, as the Article is supposed to provide, or (b) the legal bases on which the claim of territory is being made. It seems to reflect the latter. The mention of ‘law of nations’, a concept not free of ambiguity, deserves some attention as well. What exactly is referred to as ‘law of nations’ – a concept defined by many writers including Vattel, Grotius, Mill, Hobbes, et al.? In fact, the term is regarded as archaic and in modern usage already replaced by ‘customary international law’.

It is understood that the part relating to ‘judgments of competent international courts or tribunals’ is mentioned in recognition of the South China Sea (SCS) Arbitration Case between the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As can be observed, the sentence appears to have been taken from Article 38 of the International Court of Justice Statute, which is understood as providing for the sources of international law. (Thus, this bolsters the observation that the paragraph functions more as explaining the sources of Philippine territorial claims under the Federal Constitution rather than defining its scope.) More importantly, if the drafters of this provision have the SCS Arbitration case in mind, then there seems to be confusion between issues of sovereignty and maritime entitlements. Over the former, the arbitral tribunal had no jurisdiction and consequently could not and did not address the same. It appears that this sentence concerns the Federal Republic’s adherence and/or reference to international law and rules or norms arising therefrom, and is not quite a description of the extent of national territory.

The Consultative Committee properly excluded the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from the scope of Philippine territory. They are not part of our national territory over which the Philippines has sovereignty. The authority for this statement is international law, particularly the LOSC, on which the Philippines as a matter of fact anchored its case against the PRC in the SCS Arbitration Case. The LOSC is crystal clear that ‘the sovereignty of a coastal State extends […] to an adjacent belt of sea, described as the territorial sea […] and to ‘the air space over the territorial sea as well as to its bed and subsoil’. Sovereignty does not extend to areas beyond the territorial sea, e.g., the continental shelf and the EEZ. This is not to say that the Philippines is giving up all its rights in relation to these areas; it is but a recognition of international law and its regime of maritime entitlements, e.g., sovereign rights, per the LOSC. Clearly, between sovereignty, which applies to territory; and sovereign rights, which apply to the continental shelf and the EEZ, there is a huge difference that should be considered lest diplomatic tension between states is caused.

It likewise has sovereignty over other territories belonging to the Philippines by historic right or legal title.

It is understood this sentence refers to the Philippine claim over North Borneo, and states the basis of such claim.

Section 2. The Philippines has sovereign rights over that maritime expanse beyond its territorial sea to the extent reserved to it by international law, as well as over its extended continental shelf, including the Philippine Rise. Its citizens shall enjoy the right to all resources within these areas.

This section is supposed to be an assertion of sovereign rights possessed by the Federal Republic. For emphasis, such statement is permissible but may be unnecessary especially in view of our adherence to international law. Likewise, it reveals the selective appreciation of the nature of rights possessed by states in the maritime zones beyond the territorial sea given that only ‘sovereign rights’ are mentioned, without other rights such as exercise of ‘control’ and ‘jurisdiction’.

Again, for emphasis, the mention of the Philippine Rise is understandable, but what about other areas in reference to which we have or may have a right to establish the limits of an outer continental shelf as well? Without meaning to undermine the importance of the Philippine Rise and our successful establishment of the limits of an outer (extended) continental shelf in said region, the reference thereto seems superfluous; after all, the Article does not mention Boracay Island, Camotes Sea and the like, in reference to the islands and waters within the Philippine Archipelago.

The last sentence of the section is not free from controversy, and might be a source of confusion, as well. To begin with, under international law, the regime of continental shelf is characterized by exclusivity already, such that ‘if the coastal State does not explore the continental shelf or exploit its natural resources, no one may undertake these activities without the express consent of the coastal State.’ This statement therefore appears unnecessary.

Moreover, one cannot help comparing this sentence with a similar provision in the 1987 Constitution stating that the use and enjoyment of marine wealth are reserved exclusively to Filipino citizens. The omission of the word ‘exclusively’ therefore assumes much importance and might be suggestive that under the Federal Constitution, our right over the outer (extended) continental shelf is not characterized by exclusivity. In addition, the phrase ‘all resources’ may be problematic given that sovereign rights in favor of a coastal state per international law refer only to natural resources.

Lastly, because of this sentence, one might have the impression that the Philippines is claiming sovereign rights even to the resources in the water column above the outer (extended) continental shelf. This idea will then be legally inaccurate given that the superjacent waters of the outer (extended) continental shelf is covered by the regime of the high seas and is outside the jurisdiction of any state.

The wording of the article on National Territory in the Draft Federal Constitution shows a significant departure from that of the pertinent article in the 1987 Philippine Constitution. The draft constitutional provision on National Territory seems to unnecessarily speak of the legal status of the national territory, the bases of the Federal Republic’s claim of territory and the Federal Republic’s principles and policies. National territory can be sufficiently described as comprising the islands and waters of the Philippine archipelago as defined by the archipelagic baselines, certain areas outside said archipelago based on historic right or legal title, the territorial seas generated by them and the subsoil or seabed and the superjacent airspace.

Atty. Julius A. Yano is presently a lecturer at the IMO – International Maritime Law Institute in Malta, and a member of the Institute for Maritime and Ocean Affairs (imoa.ph). The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any organization or his affiliations.