For the past few decades, the world experienced a big shift on how information is gathered and disseminated. The internet became a connection which is virtually unlimited. Today, it is norm to have free information – something which is uncommon during the days prior to the conception of the internet. Almost every information is already posted in the world wide web and can be downloaded for free. The National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA), which is the central mapping agency of the Government of the Philippines (EO 192), has also followed the step towards free information by designing and maintaining the Philippine Geoportal. Users can browse or search geospatial data and download them through the Geoportal. They can also share their data by uploading it through the same portal. Previous to the Philippine Geoportal, hydrographic data and paper charts are only given for a fee even for other government agencies. Nowadays, almost every sector is providing free information.

Aside from being the central mapping agency, NAMRIA is also the National Hydrographic Office of the country. It is the agency representing the Government of the Philippines in the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) which is based in Monaco and its regional group East Asia Hydrographic Commission (EAHC). The IHO is an intergovernmental consultative and technical organization that was established in 1921 to support safety of navigation and the protection of the marine environment (www.iho.int). The official representative of each Member Government/State within the IHO or its regional group is normally the National Hydrographer or the Head of the National Hydrographic Office.

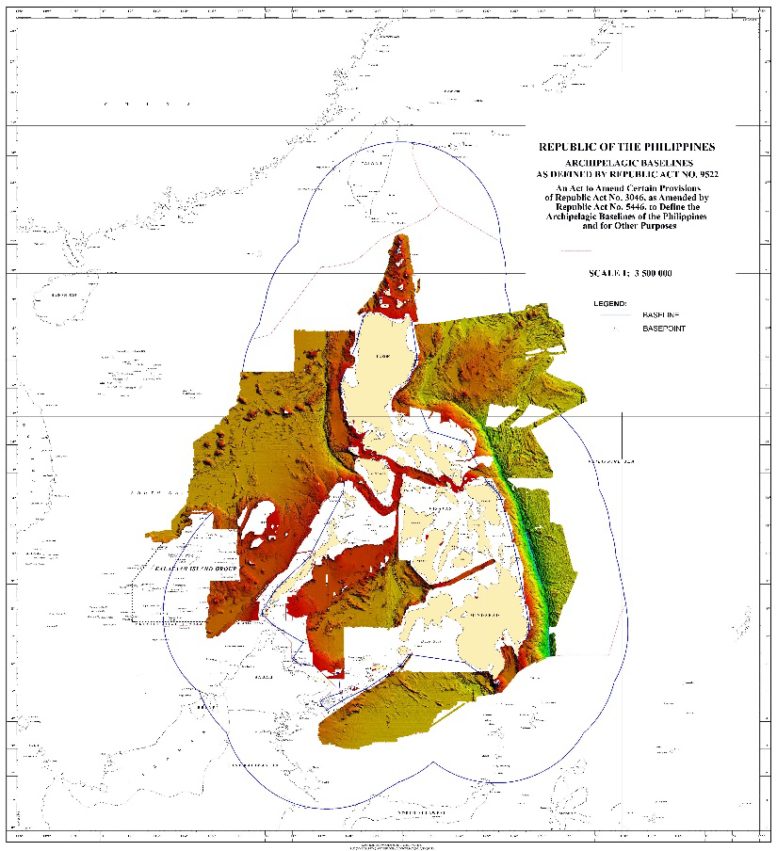

Currently, NAMRIA is the only government agency of the Philippines conducting hydrographic survey to produce nautical charts. It is responsible for the survey of all Philippine waters such as the Archipelagic Waters, Territorial Sea, and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Hydrographic survey includes among others bathymetric survey, coastline topographic survey and physical oceanographic observations. Bathymetry as defined by the IHO Hydrographic Dictionary is “the determination of ocean depths” (p. 23). The same dictionary defines hydrography as “that branch of applied science which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of the navigable portion of the Earth’s surface and adjoining coastal areas, with special reference to their use for the purpose of navigation” (p. 108). With the limited resources of the government, not all of the Philippine waters have been surveyed accurately. Only 25% of the Philippine waters below 200 meters have been adequately surveyed (IHO C-55, 2016, p. 355). The remaining 75% either need resurvey or have never been surveyed. Areas deeper than 200 meters are also similarly not surveyed sufficiently. Only 30% of waters more than 200 meters deep have been surveyed (IHO C-55, 2016, p. 355).

Figure 2. Multibeam Bathymetric Surveys

Note. Bathymetric surveys are focused on sea lanes (colored green). Beyond those areas, they are virtually unsurveyed accurately. The image was adapted from https://maps.ngdc.noaa.gov/viewers/bathymetry/.

The situation of the Philippines is not different from the global condition. In the 2017 Input to Part I of the Report of the UN Secretary General on Oceans and law of the Sea, IHO stated that “less than 15% of the depths of ocean waters (>200 metres) have been measured directly and about 50% of the coastal waters (<200 metres) remain unsurveyed” (p. 1). Thus, the statement “mankind has higher resolution maps of the Moon and Mars than for most of the seas and oceans” (Input to the Report of the UN Secretary General on Oceans and Law of the Sea, 2013, p. 1).

Will there be problems if the majority of Philippine waters is not surveyed accurately?

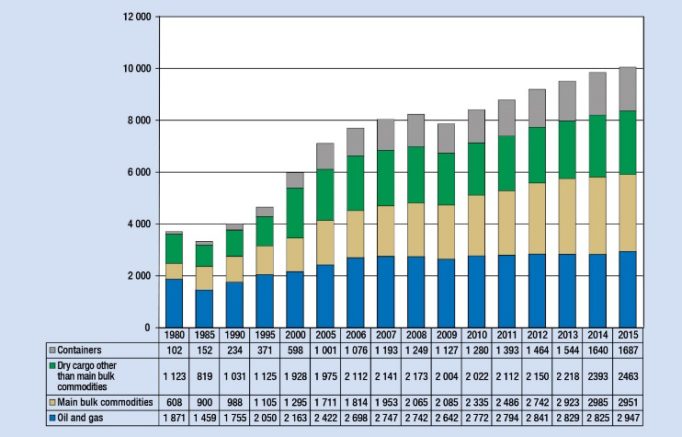

Maritime transport is critical in world trade. It is very important for an archipelagic State like the Philippines whose goods are transported among its islands, almost all through maritime transport. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) International Shipping Facts and Figures – Information Resources on Trade, Safety, Security, Environment (2012) stated, “it is generally accepted that more than 90% of global trade is carried by sea” (p.7).

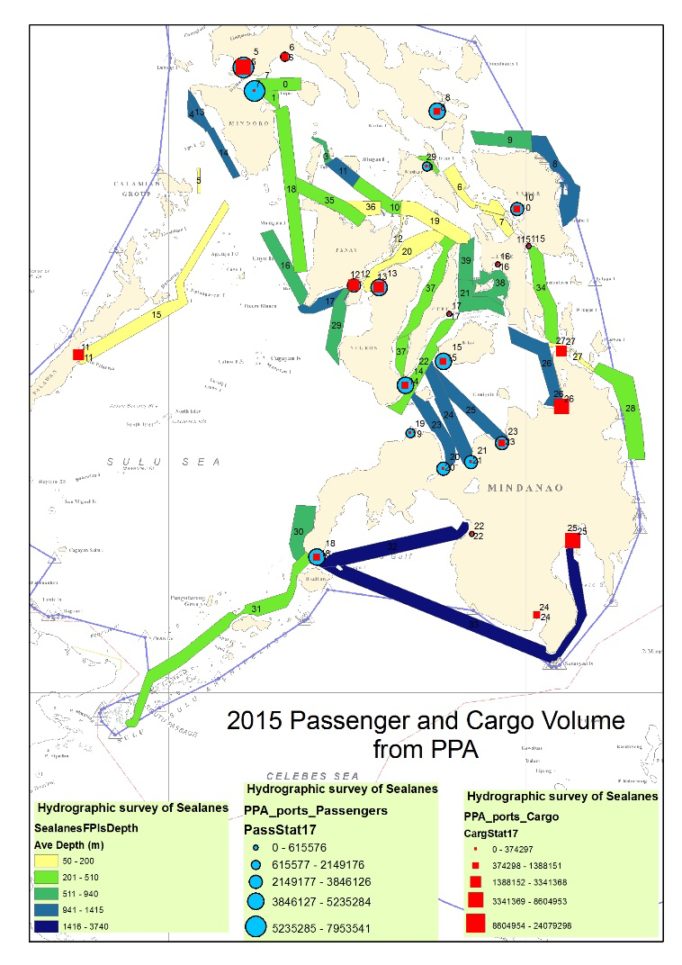

Figure 3. Maritime Routes for Passengers and Cargo. Note. The colored areas represent the maritime lanes used for transport of passengers and cargoes among the islands of the Philippines. The image was adapted from the Hydrographic Data Management Section of the Hydrography Branch using 2015 PPA Data, NAMRIA.

There are almost two million seafarers and over a hundred thousand of ships travelling around the globe. “As at December 2010, today‘s world fleet of propelled sea-going merchant ships of no less than 100 GT comprises 104,304 ships of 1,043,081,509 million GT with an average age of 22 years; they are registered in over 150 nations and manned by 1.5 million seafarers of virtually every nationality” (International Shipping Facts and Figures – Information Resources on Trade, Safety, Security, Environment, 2012, p.9). The figure does not even include small vessels used for recreation or small-scale activities.

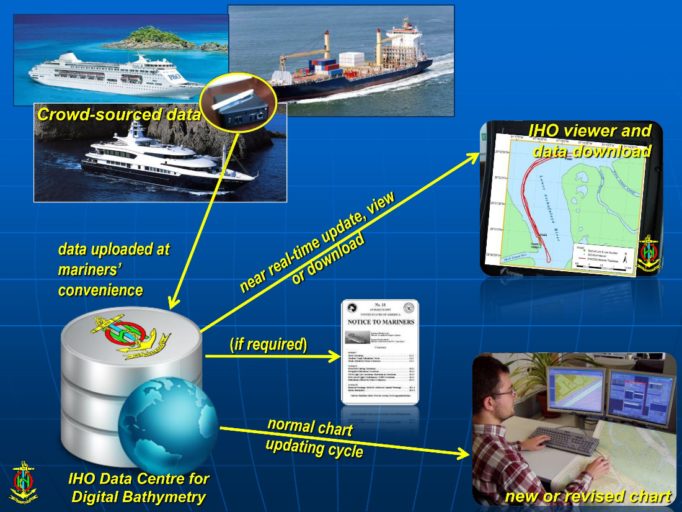

With the increasing number of seaborne trade, there is also an increasing need for a more accurate seafloor mapping. Accurate mapping is a prerequisite to producing a nautical chart. Despite the increase in maritime activities, many hydrographic offices have claimed that national hydrographic survey activities are being reduced because of conflicting priorities of their government. In order to supplement the survey conducted by national hydrographic offices, the IHO has suggested that crowdsourced bathymetry be encouraged and promoted by all stakeholders in its Input to the Secretary General to the UN (2017, p. 4). Crowdsourced bathymetry (CSB), as defined by the IHO website is a collection of depth measurements from vessels, using standard navigation instruments, while engaged in routine maritime operations.

Figure 4. International Seaborne Trade. Note. The left column is expressed in millions of tons. The seaborne trade in 1980 was less than 4 Billion Tons. It grew to more than 10 Billion Tons in 2015. The image was adapted from Review of Maritime Transport, 2016, p. 7.

As a member of the IHO and EAHC, NAMRIA is mandated to abide by IHO and EAHC rules and regulations. With the recommendation of IHO for all member states to adopt CSB, Philippines might have no choice but allow it inside its waters. The concept of CSB allows virtually anyone to have an echo-sounder on his vessel and gather bathymetric data. Permission of the Coastal State may not be sought. In crowdsourcing, anyone can survey and anyone is also allowed to view the data. In other words, bathymetric data will be free and available to anyone.

Figure 5. Crowdsourced Bathymetry (CSB) Diagram. Note: Data are uploaded at the mariner’s convenience and can be viewed in real-time by anyone with a viewer. Adapted from PowerPoint Presentation Overcoming the Lack of Hydrographic Data (n.d.).

Implication

Free bathymetric data through crowdsourcing is definitely a good source of supplemental data for the safety of navigation. It is also beneficial to the scientific community to further explore and exploit the sea. However, the unique situation of the Philippines makes it uncertain whether such bathymetric crowdsourcing brings more benefit than harm. If bathymetric crowdsourcing is allowed, there is no reason for the Coastal State to stop other states to collect bathymetric data using their own equipment. This freedom may bring forth problems specially when the data is collected by unfriendly forces. It cannot be denied that the Philippines and its waters is a strategic location for both aerial and maritime warfare. This may be the reason military why hegemons like US and China are conducting hydrographic surveys within and around the Philippine waters.

In early 2017, news broke out about Chinese vessels conducting hydrographic survey in Philippine waters. Steven Stashwick, in his article in The Diplomat (2017) pointed out, “detailed hydrographic information of the area would be critical to helping China’s submarines evade U.S. efforts to find them.” Several TV reports in 2017 have shown that Chinese military vessels have been spotted as far as East of Surigao conducting what appears to be hydrographic survey. Earlier in 2016, China’s Navy seized an American underwater drone near the coast of the Philippines. Unwillingly, the Philippines seems to be examined and planned by the hegemons as a venue for naval warfare.

The Philippines must study whether it will benefit by allowing CSB within its waters. It may have a hard time determining whether hydrographic survey activities conducted by foreign vessels are for safety of navigation which is allowed under the UNCLOS or for other purposes. It is easy for vessels of foreign origin to conduct bathymetric survey for their military use but pretend to be as CSB. Despite the limited capability of the Philippine government, it may be wise that CSB should still be regulated considering the position of the Philippine Islands as a good location for both defensive and offensive attacks in times of war in the Pacific area.

It will not take long before CSB goes into mainstream. The IHO has already composed a Crowdsourced Bathymetry Working Group (CSBWG), comprising representatives from national Hydrographic Offices, academia, and industry. Last June 2015, the Terms of Reference for the CSBWG was approved by the IHO Inter-Regional Coordinating Committee in Mexico City. Also, CSB must be defined accurately to eliminate issues with the provisions of UNCLOS. Article 19 of UNCLOS that “Passage of a foreign ship shall be considered to be prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State if in the territorial sea it engages in any of the following activities: …(j) the carrying out of research or survey activities” (1982). Clearly, the provision covers survey activities such as bathymetric activities.

This is the right time for our lawmakers to pass the Maritime Zones Bill which is long overdue. The Bill may not directly answer whether CSB be allowed or not but it will limit the movement of foreign vessels within the Philippine waters. Without definite sea lanes, navigators may claim that their route are generally accepted and can conduct hydrographic survey for military purposes in the guise of crowdsourced bathymetry.

Crowdsourced bathymetry was conceptualized to support hydrographic activities with the ultimate goal of protecting life and property during navigation at sea. Free information improves efficiency and cost effectiveness of national hydrographic offices. However, we must also ensure that free information such as bshould not be prejudicial to the interest of the Coastal State.

About the Author. Lieutenant Commander Carter Luma-ang is a Hydrographic Survey Officer of NAMRIA. He graduated from both the Rhodes Academy on Ocean Law and Policy (2012) and Yeosu Academy on Ocean Law and Policy (2014). He earned his Category B Hydrographic Survey from the Japan Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department (2006). He also earned his Master in National Security Administration from the National Defense College of the Philippines (2016).

References:

Butt, N., Johnson, D., Pike, K., Pryce-Roberts, N., Vigar, N. (n.d.). “15 Years of Shipping Accidents: A review for WWF.” Southhampton Solent University, p. 56.

International Hydrographic Organization (2013). “IHO Input to the Report of the UN Secretary General on Oceans and Law of the Sea.” IHO, p. 4.

International Hydrographic Organization (2017). “IHO Input to Part I of the Report of the UN Secretary General on Oceans and Law of the Sea.” IHO, p. 4.

International Hydrographic Organization (2016). Crowd-Sourced Bathymetry [PowerPoint Slides presented to the NIOHC 2016 at Chittagong, Bangladesh]. Retrieved from https://www.iho.int/mtg_docs/rhc/NIOHC/NIOHC16/NIOHC16-12-Crowd_Sourced_Bathymetry.pdf

International Hydrographic Organization (n.d.). Overcoming the Lack of Hydrographic Data [PowerPoint]. Retrieved from https://www.iho.int/mtg_docs/rhc/MACHC/MACHC14/MACHC14-10.3-CSB-RW.pdf

International Hydrographic Organization (2016). “IHO Publication C-55.” Monaco, p. 528.

International Maritime Organization (2012). “International Shipping Facts and Figures – Information Resources on Trade, Safety, Security, Environment.” Maritime Knowledge Center, p. 47.

Stashwick, S. (2017). “China May Have Been Surveying Strategic Waters East of Philippines.” The Diplomat. 31 March 2017. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2017/04/china-may-have-been-surveying-strategic-waters-east-of-philippines/

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (10 December 1982).

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2015) “Review of Maritime Transport.” United Nations. P. 108.