Some researchers contend that a sovereign state has three (3) interrelated functions in the maritime domain: maritime safety, maritime security and

maritime defense. These functions require legislation, compliance to some international conventions, and executive issuances that are directed to various maritime agencies.

Maritime safety, the first function, refers to actions that promote safety of life at sea including search and rescue, aids to navigation and notices to mariners, avoidance of sea collisions, hydrographic surveys, ship and port safety inspection services, anti-marine pollution prevention and mitigation, and seafarers’ training and qualifications. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) promulgates most of the maritime safety guidelines and

each membercountry either entirely adopts the IMO’s policies and/or issues rules for local application.

Maritime security, the second function, involves joint or uni-service operations to prevent, detect and suppress illegal activities in the maritime

zone. These illegal ventures include piracy, terrorism, illegal migration, exploitation of sea resources, as well as smuggling of contraband, people, and weapons of mass destruction. This function entails surveillance, interdiction, and enforcement operations.

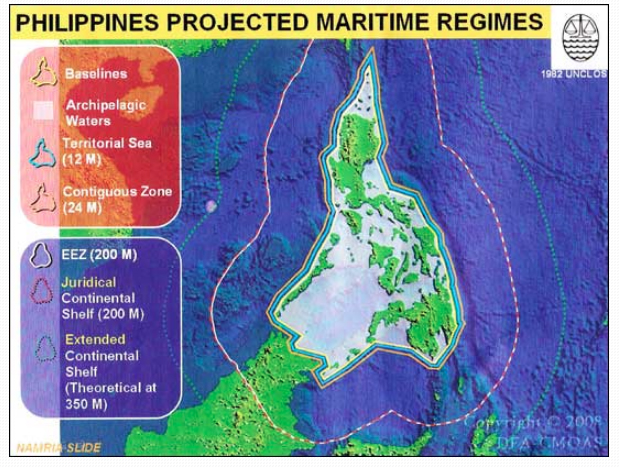

Maritime defense, the third function, calls for defending the territorial integrity, and protecting the sea lines of communications and other inshore and offshore assets. It provides assistance in crisis and distress situations. Maritime defense aims to establish control of the maritime zones or deny the competitor of such control by use, or threat of use, of force, and continuing presence of combatant ships, other seagoing forces, and domestic merchant/fishing vessels.

The withdrawal of American forces in the early 1990s and the depletion of fishery resources in an adjacent sea gave China, a neighboring country, an opportunity to “fill the vacuum” invoking baseless “historical rights” in contravention of international law, in the pursuit of its hegemonic ambition. In

1995, China occupied Panganiban (Mischief) Reef, a traditional sheltering feature of Filipino fishermen in the Spratlys. In turn, the Philippines converted its stranded naval transport ship in Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal, some 20 miles east of Panganiban Reef, into a military detachment to preserve the marine resources inside the shoal and dissuade others from occupying it. Years later, China fortified and eventually transformed the reef into a military base along with two other features in the vicinity thereby effectively militarizing the South China Sea. In 2012, China took control of Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal, situated 124 nautical miles west of Zambales, well within the Philippines’ EEZ of 200 nautical miles, and denied our

fishermen access to marine resources to their traditional fishing ground.

Since then, and even with our victory in the 2016 PCA Ruling of our legal rights in international maritime law, Chinese coast guard and maritime militia ships have and continue to freely roamed the Spratlys akin to ownership. This is tantamount to sea control. Many of these vessels enter our EEZ boundaries and they limit our fishermen’s legitimate movements, harass small replenishment boats to the Ayungin Shoal detachment, and confront Philippine research vessels in Recto Bank. Reports from domestic and international sources indicated that Chinese government ships intrude and conduct illegal research in Philippine waters, including the Philippine Rise.

In one incident a Chinese fishing vessel rammed a Filipino fishing boat F/B GemVer while fishing west of Palawan and abandoned the crew as the boat slowly sank. In another, Chinese government vessels confronted our government commissioned survey ship in Recto Bank, well within our EEZ, and warned us of unpleasant consequences if we exploit gas and oil in that area. The Philippines has filed numerous diplomatic protests for these harassments and unauthorized presence but obviously they fall into deaf ears.

By exercising a semblance of “control” in the Spratlys, Panatag Shoal and in the northern portions of the Philippine Sea including Philippine (Benham) Rise, China has demonstrated its enormous capability through its PLA and maritime militia as a maritime power. In addition, China apparently sends a strong signal to Taiwan that PLA forces could flex muscles to attain the ultimate objective for reunification. The recent maritime exercises involving live firing of guns and missiles by air and naval units in defined maritime areas surrounding Taiwan before, during, and after U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit, displayed the positive effect of PLA’s streamlining plan initiated in 2016. The plan reduced the PLA strength by 300,000 troops,

lessened the number of field command headquarters, created new strategic commands and upgraded its capabilities with the maritime forces on top of the priority list. Not only did the Chinese strengthen their grip on the South China Sea but they also expanded their global reach to protect their maritime belt road initiative. The reduction of troops and units’ command structure allowed the channeling of budget to military modernization to

improve China’s warfare capabilities in the 5-dimensional battle space, including electronic and information cyber warfare.

China’s force restructuring is obviously conceived and realized to pursue its maritime strategy in South China Sea and to protect the maritime belt road initiative that passes through the Indian Ocean and beyond towards Europe and Africa. The South China Sea strategy consists of 4 reinforcing actions: (1) Ignore the 2016 PCA ruling; (2) Reinforce control of artificial islands using coast guard patrols and intensified maritime militia presence; (3) Use of economic leverage to demand compromise; and (4) Squat in the occupied features until other disputant nations give up. In the Philippine eastern seaboard, the Chinese continue to conduct, with or without permission, oceanographic surveys, possibly for resource exploitation, submarine detection, and cable laying. Those surveys include identification of underwater features, and the use of Chinese names to indicate ownership. There have been reports of Chinese non-merchant vessels supposedly just passing through our straits but linger in our territorial waters without seeking permission from the authorities.

China’s presence and activities in the country’s peripherals cannot go on indefinitely lest the nation’s patrimony for

the future generations irreversibly depletes because of insensitiveness and cowardice to assert our sovereignty and sovereign rights. Defending our maritime zones is complicated. Diplomacy has always been the nation’s first line of defense. But it has limitations as proven by the non-action of China in the numerous diplomatic protests forwarded to that country in the near past.

The creeping “invasion” of our maritime zones using gray zone or hybrid strategy is breaching our physical outer line of defense. As several defense analysts and retired military officers observe: there may be a need to recalibrate the operational strategy of the armed forces. The lead military analyst and his cohorts’ view is partly anchored on survey results two years ago resulting from the F/B GemVer incident: Filipinos want to protect our West Philippine Sea (WPS) and other maritime zone areas from foreign exploitation and to continue the armed forces modernization. Political realities, however, prevent full scale defense capability development. Instead, with its limited budget the armed forces may consider the review of the military

hardware in the priority list to identify the most vital equipment that would put flesh to a “credible defense” posture in the maritime domain. The focus should be on the lethality and reach of the armaments, and the survivability of the weapons delivery platforms.

Such definition of a “credible defense” is a departure from a previous view that merely showing your presence where the intruders are would constitute “credibility.” The financial limitation will involve subjecting the weapons acquisition list to iterative selection process. In tandem with the other pillars of the modernization, force structuring is a must just like in other militaries with finite financial resources and clear identification of specific threatened areas or red lines. Force streamlining would call for recalibration of the ISO-focused operational strategy. The land forces will concentrate in the country’s land and territorial sea boundaries; while a new joint command structure to be known as maritime command reports directly to general headquarters. Consisting of air and naval forces, the maritime commands will cover the contiguous zone up to the EEZ and continental shelf. For synergy, some coast guard units shall be attached to the maritime commands under certain top-level arrangements to perform maritime safety and security duties; while civilian affiliated units will operate in specific maritime areas for monitoring purposes while on legitimate ventures.

The maritime commands will be in a better position to formulate their doctrines including rules of engagement; assess the joint force’s manpower level, equipage, sustainability and readiness; identify the capabilities for detection, target acquisition, neutralization and force protection; prioritize

employment of weapons; assign civilian affiliated units’ monitoring areas and update the national command authorities on real time on significant maritime operations. The expanse of the sea for better command and control would be divided into three maritime commands: Western (WPS, Spratlys, and Sulu Sea), Northern (North of WPS up to Luzon Strait) and Eastern (Pacific side EEZ including Philippine Rise down to northern Sulawesi Sea). The existing combatant commands will continue to decimate the local communist armed insurgents and prepare assigned regular forces and territorial reserves to counter any invasion.

The likelihood of foreign aggression is difficult to predict but defending territories, sovereign rights and the people and their way of life cannot and should not be abandoned by any self-respecting nation. As many great military commanders have learned in the past: to preserve peace, one must prepare for war. We must prepare to fight for peace. We must fight to prevail. As we defend our maritime zones our political and armed forces leadership must know how the enemy thinks, and likewise heed Sun Tzu’s advice, but most importantly– act expeditiously:

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained, you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself,”