“The more we work together, the merrier we’ll be.” Or so the popular lullaby goes.

However this does not ring true for the Philippine domestic ships with an overwhelmingly large number of cadets onboard. The European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) Report conducted last year states, “The team found cases in which 11, 16 or even 37 deck cadets were onboard those [inter-island] ships, on which there were only two deck officers and the master.”

This report was revealed during the virtual workshop held 11-12 March 2021 spearheaded by the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA). This event is geared to consult with industry stakeholders and their technical expertise especially in the fields of maritime training and maritime higher education institutions (MHEIs) to address the EMSA concerns. The Europe-based agency found 13 shortcomings and three observations in its inspection last year. One of these is the overwhelming quantity of cadets serving on a Philippine domestic ship.

The EMSA team proposed a “review and revision of Marina Advisory 2020-11 in the categorization of ships registered regarding the number of cadets to be accommodated on domestic ships as stipulated in MA 2020-11 in the conduct of structured training in the training ship consistent with Maritime Labor Convention (MLC) 2006.” This will yield a reduction in the number of cadets that domestic ships could accommodate for on board training (OBT).

This strategy, however, was denounced by Philippine Association of Maritime Institutions (PAMI) President Sabino Czar Manglicmot II saying that many maritime schools “would likely cease operations if the government will restrict the number of cadets who will undergo OBT” on inter-island vessels. “I heard there was a recommendation for limiting the berths for a cadetship. I would object to it. We would like to have it increased. There should always be partnership between private maritime education and the shipping companies to also include the government,” he emphasized.

With only two officers and a master supervising the cadets, is “on board training” (OBT) adequate? Is there sufficient support for their education and is it being monitored properly? Or are these young sailors just being used as cheap labor?

The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers 1978 (STCW), as amended, “recommends that Administrations make arrangements to ensure that shipping companies encourage all officers serving on their ships to participate actively in the training of junior personnel.” (source: Resolution 7, paragraph 4, subparagraph 3 of the STCW Convention.)

Sadly, this is an unbelievable reality in some ships. There are domestic vessels with more cadets than experienced seafarers. The main reason is obviously to reduce wages. Consequently, the tasks supposedly for able-bodied seamen have been streamlined and delegated to cadets.

One of the frequently asked questions is: Are cadets considered seafarers despite their relative newness in the profession? MLC 2006’s response: “On the assumptions that cadets are performing work on the ship, although under training, they would be considered as ‘seafarers.’ Emphasis should be given on ‘under training.’ Their primary purpose is to acquire practical knowledge in application of what they were taught in college. They are new to the shipping industry and are still in need of guidance. They need to be integrated in the maritime operations both theoretically and in application.”

Per STCW Circular 2017, Responsibility of the Company in Shipboard Training, #10: The proposed ratio of onboard training officer for deck or engine to the candidates is 1:12 to have an effective training and assessment.

But what happens when there are more than a dozen cadets on a ship? Is mentoring still present or have they become substitute workforce doing the tasks of more experienced seafarers? Can the officers still “monitor carefully and review frequently the progress made by junior personnel in the acquisition of knowledge and skills during their service onboard ship” as recommended by STCW?

To efficiently train, it will be most beneficial if it follows the APEM system of effective voyage planning — appraise, plan, execute, and monitor.

The figure below gathered its information from Training and Assessment On Board by L.A. Holder, with the additional APEM subdivisions, which I added.

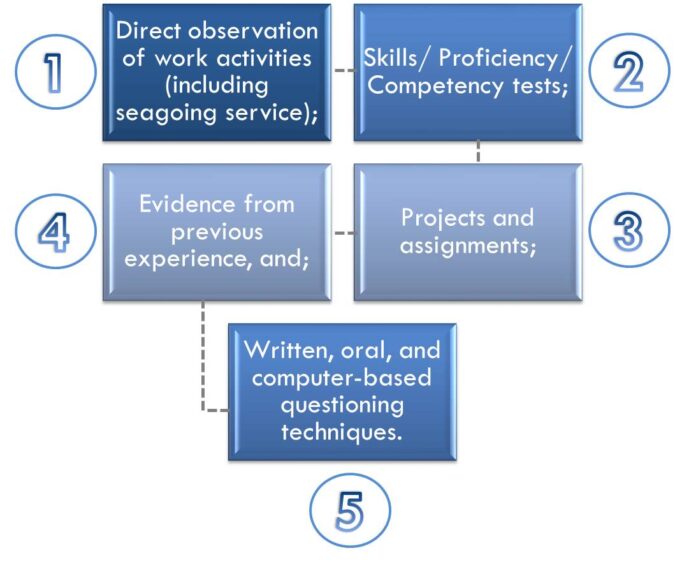

Then observe the trainees’ progress and employ assessment methods. The STCW Code Part B/II 17 offers guidance on some techniques on how to assess competence. “The arrangements for evaluating competence should be designed to take account of different methods of assessment which can provide different types of evidence about the candidate’s competence.”

Others may still be hesitant, arguing: “what will they gain from training and coaching others? Is it not just an additional workload for them; after all they are not paid to become teachers? These cadets will just learn after prolonged exposure in the ship operations!” Those are the mindsets that the industry has to let go.

STCW Resolution 13 states: “the lack of adequate accommodation for trainees on board ships constitutes a significant impediment to properly training them and subsequently retaining them at sea, thus adding to the aforementioned shortage” [of qualified officers to effectively man and operate ships engaged in international trade]. To supply this inadequacy and to keep up with global standards, Manglicmot asked help from MARINO partylist Cong. Macnell Lusotan, who was present at the workshop.

“I am very happy that Cong. Lusotan is here; maybe MARINO partylist could introduce some sort of economic benefits to domestic shipping companies that would accommodate cadets [on their ships],” Manglicmot said.

“We need to compete with our neighbors in manpower. One way that we could compete with them is to send out more cadets, more officers. This is the way we should go,” he added.

There was no response from Cong. Macnell Lusotan.

This year, the theme for the International Day of the Seafarers as decided by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) will be “Fair Future for Seafarers.”

In the discussion of fairness, may we remember the cadets and early maritime professionals who will be the future of the seafaring industry. Years from now, these 64 cadets that the EMSA noted, along with many others, will be the officers steering at the helm. Questions loom. Have we prepared them enough for what may lie ahead? Or are we more focused on quantity over quality? Is more always better?

Private shipping companies who only look at bottom line profits and put cost savings as primary, are what will drag the ships down, at the expense of the cadets and junior seafarers who are denied the proper practical training by experienced seafarers onboard.

Decisions affect our cadets and seafarers well into the future. High quality education and training are crucial to preserve the quality, caliber of maritime skills and technical competence of qualified seafarers in keeping sea-going vessels safe, protecting the environment, and keeping trade flowing.

About the author:

Yrhen Bernard Balinis is an ordinary seaman (with extraordinary goals) and a promising maritime journalist. His articles have been published by international maritime-related journals including Seaways, Navigation News, and Safety4Sea. He is currently serving as a member of The Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN); an associate member of The Nautical Institute (NI); and a student-member of The Institute of Marine Engineering, Science and Technology (IMarEST). Yrhen Bernard envisions a more inclusive, sustainable and technologically-advanced maritime industry. You may contact him via www.linkedin.com/in/ybsbalinis.