“ Coast Defense, in its broadest sense, includes all measures

taken to provide protection against any form of attack at

or near the shore line as well as within the combat zone

immediately in rear thereof. ”

-US FM 31-10 Basic Field Manual of Coast Defense

INTRODUCTION

In October 2019, the Philippine Army activated the Artillery Regiment’s 1st Land-Based Missile System Battery and 2nd Multiple Launch Rocket System Battery at Fort Magsaysay in Nueva Ecija. Ten months later in August 2020, the Philippine Navy activated the Coastal Defense Regiment (CDR) of the Philippine Marine Corps at Marine Barracks Rudiardo Brown, Headquarters Philippine Marine Corps, Taguig City. The CDR’s functions were designed to protect the country’s coast, shores, ships, and amphibious task forces from an invading enemy and to improve support of naval operations.

The aforementioned units were activated in anticipation of the acquisition of India’s Brahmos Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles and the arrival of the Republic of Koreas Kooryong K136 Rocket Artillery System for both the Philippine Army and Philippine Marine Corps.

By April 2021, the Philippine Marine Corps unveiled its new warfighting concept –the Archipelagic Coastal Defense as part of an inter-agency– an integrated Joint Operations which also adds to the Philippine Navy’s Active Archipelagic Defense Strategy (AADS) all geared toward an External Defense Posture and of the Anti-Access/Area Denial or the A2/AD concept prevalent with the Western Naval Forces.

Most recent is the release of the special allotment order of the 15% initial down payment for the Philippine Navy’s Shore-Based Anti-Ship Missile System –the acquisition of the Brahmos AS Cruise Missiles.

These weapons systems would play a pivotal role for the defense and security of the world’s second largest archipelago, which has more than 7,600 islands and boasts a total coastline of 36,289 kilometers. The Philippines is no stranger at taking an enemy from the sea that dates back to the ancient period up to the Second World War, and which this paper seeks to explore.

COASTAL DEFENSE IN PRE-COLONIAL PHILIPPINES

Prior to the Battle of Mactan, there were already antecedents in Pre-Hispanic Philippines of Raiders coming from the Sea as the rulers between Islands fought for control of territory and economics such as the conflict between the Rahjanate of Cebu and the Sultanate of Maguindanao.

Another would be the conflict between Rahjanates of Manila and Tondo which were at the Country’s Center of Gravity. The Battle of Mactan is unique as it is the most well-known first recorded native resistance to a European power.

Coastal Defense Actions were already prevalent in Pre-colonial Philippines in which the maxims of beach defense and anti-landing concepts were already in effect.

Battle of Mactan: First Coastal Beach Defense Operation (27-April-1521)

Painting by Carl Frances Morano Diaman shows the Battle of Mactan exhibited at the Lapu-Lapu Shrine in Mactan Island.

Marking its Quincentennial Anniversary last year, the Battle For Mactan could also be considered as the known First Beach Defense Operation in the Philippines.

The Commanders:

DATU Lapu-Lapu (Local Chieftain of Cebu) Captain Ferdinand Magellan (Spain) (Expedition Head).

Strength of Forces:

Datu Lapu-Lapu had amassed strength of about 1, 500 warriors, while Ferdinand Magellan had 5 ships and 270 men.

On a Bloody Shore:

The Spanish Soldiers under Ferdinand Magellan held the advantage against Lapu-Lapu’s force but were defeated for their over-confidence despite their logistical problems. Apart from the 60 Spanish Soldiers, Magellan was accompanied by a local chieftain and his warriors which were never deployed during the battle. Magellan’s forces possessed the weaponry and armor but lacked the employment of additional manpower and naval gunfire support both of which ultimately cost them defeat at the hands of Lapu-Lapu.

The Chieftain of Mactan and his forces utilized to their advantage the terrain, and had a good grasp of the vulnerability of the Spanish armor suite hitting them on the bare areas of their body. Additionally, their weighted armor once in the water reduced their mobility. One aspect was Lapu-Lapu’s men consistently followed through their attacks with manoeuvre warfare and armed their spears and crossbows with poisoned arrows as secondary weapons.

Despite superiority and modern technology by invaders of that era, the beach defense maxims were successfully implemented by the local warriors of Mactan, denying the enemy the occupation and seizure of Mactan.

The Ships of the Armada De Moluccas

On 20-September-1519, the Royal Commission was sent off designating Capitan Fernando De Magallanes to head the Expedition in search of the Spice Islands. Flotillas of five ships were tasked for the expedition, namely:

- The Trinidad (Flagship) with Ferdinand Magellan as Captain;

- The Santiago under Capitan Juan Rodriguez Serrano;

- The San Antonio under Capitan Juan De Cartagena;

- The Concepcion under Capitan Gaspar De Quesada; and

- The Victoria under Capitan Louis De Mendoza.

Of the 5 ships, only the Victoria made it back to Spain.

Lessons Learned:

ADVANTAGE OF TERRAIN: Lapu-Lapu and his men were able to take advantage of the local terrain and the shoreline, the Spaniards with their heavy armor suffered reduced mobility to move in water.

STRENGTH: With quite a disparity from the start, the Spaniards assumed that with their advanced technology they would easily defeat Lapu-Lapu’s warriors, despite being outnumbered.

NAVAL GUNFIRE SUPPORT: The cannon and mortars on Magellan’s Ships and the crossbows of the local warrior on board Magellan’s ships and Balangays were never utilized against Lapu-Lapu’s warriors as they were out of range and the ships were anchored too far away from shore.

STRATEGY AND TACTICS: Again with the advantage to terrain, the invaders from the start had already lost in terms of manoeuvre as they were pinned down and engaged in a frontal and pincer manoeuvre of Lapu-Lapu’s Forces. One should have a means of escape or extraction point for the soldiers to cut and run, else they get captured or killed. Lapu-Lapu would have seen this particular advantage even before the Spaniards lowered down their boats to get to shore.

COASTAL DEFENSE IN THE SPANISH PERIOD

During the Spanish occupation of the Philippines, the essence of Commerce Raiding and Coastal Defense were ample be they against foreign or domestic pirates.

These piratical raids had already taken a toll on Spanish prestige and economy at that period. Hence, Operations were planned by as early as 1848 right up to the Philippine Revolution in curbing out the threat of piracy in the archipelago specially in the Southern Waters.

In the narrative below, first covering the Beach Defense against the Chinese Pirate Limahong, were thwarted with the combined Filipino-Spanish Force. In this action, the Chinese Pirates failed in utilizing the essence of intelligence while the Spanish utilized it to the effect that Limahong’s forces were tracked early on at its forts and lighthouses, and their movements were reported to the Filipino-Spanish Force.

Second, the Amphibious Assault in Balanguingi Island and the reversed Coastal Defense of the Moro Pirates were again on the maxims of Beach Defense that of Seapower and sound strategy.

Lastly, the raid on the Moro Fortresses at the Rio Grande was also a classic aphorism of warfare, that of Combined arms from the Spanish Army and Marines in artillery and naval gunfire support.

The Battle of Don Galo: 29-30 November 1574

53 years after the Battle For Mactan came another Beach Defense Operation in the shores of present day Paranaque City.

The Red Sea incident as it was then known was a part of the larger Battle For Manila.

Limahong’s Forces first landed in Ilocos Norte and were able to defeat some Spanish Forces. He then sailed towards Manila and landed on Paranaque.

Captain Juan de Salcedo, Spanish conquistador in the Philippine, dated 7-July-1807. Photo Source: Creative Commons/Wikimedia.org

Captain Juan de Salcedo, Spanish conquistador in the Philippine, dated 7-July-1807. Photo Source: Creative Commons/Wikimedia.org

Limahong’s Forces had the upper hand in manpower with about 6,500 men on board 62 ships while the local force under a Filipino named Galo was around 300 men, later on with the arrival of the Spanish Army Captain Juan De Salcedo of about 300 additional men that defeated the Chinese Corsairs, with Limahong making his way towards Pangasinan.

Lessons Learned:

FAILURE OF INTELLIGENCE: One facet of beach defense, as with all military actions, is basic intelligence. In this operation, Limahong failed to utilize the various captives he had, as well as to send out a reconnaissance party. He was earlier told that Paranaque had a weak defense or none at all, or again, a victim of over-confidence.

COMMAND & LEADERSHIP: The Village Leader, Galo, aptly enabled the Command and Leadership, and rally his townsfolk into depriving the enemy of gaining a foothold to capture their village.

COMBINED WARFARE: Another aspect of this operation was Combined Warfare in which the Filipinos and Spaniards were able to integrate into a combined force which was already the practice in various Spanish Coastal Fortifications with Spanish Officers and Filipino militia.

FAILURE OF NAVAL GUNFIRE SUPPORT: Limahong, despite having a number of ships, the shallow waters and the range to shore for his artillery made them ineffective.

The Battle of Balanguingi: 16-22 February 1848

The Battle of Balanguingi Island is similar to the United States Marine Corps landing at Tripoli, Libya with the objective of curbing Piracy in the region. The Balanguingui Island is a stronghold of Moro Pirates prowling that area of Mindanao. The Spanish had had enough of the piracy and decided to take on the pirates at their lair.

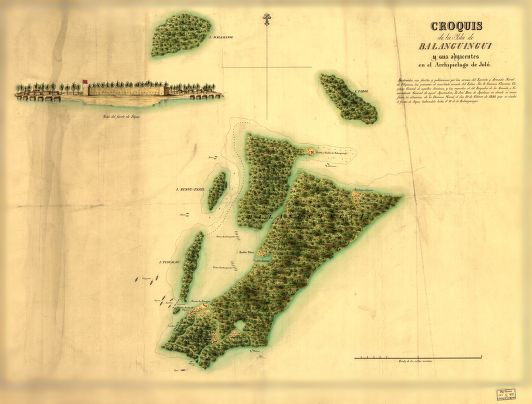

The objective was to capture the Island and the four Fortresses thereat. Balanguingui was located between the Province of Basilan and Jolo. A classic Amphibious Assault Operation by the Spanish Forces under Brigadier General Jose Ruiz De Apodaca and Lieutenant Colonel Arrieta with the overall Command of the Spanish Governor General Narciso Claveria.

Map of Balanguingui Island, 1848. Photo Credit: J. Espejo.

The Amphibious Landing at Balanguingui Island in 1848. By artist Antonio Brugada, 1804-63. Photo credit: Oronoz.com.

The Moro Pirates had the upper strength in manpower, though the Spanish Forces had in support 19 warships along with a sound concept of the assault operation.

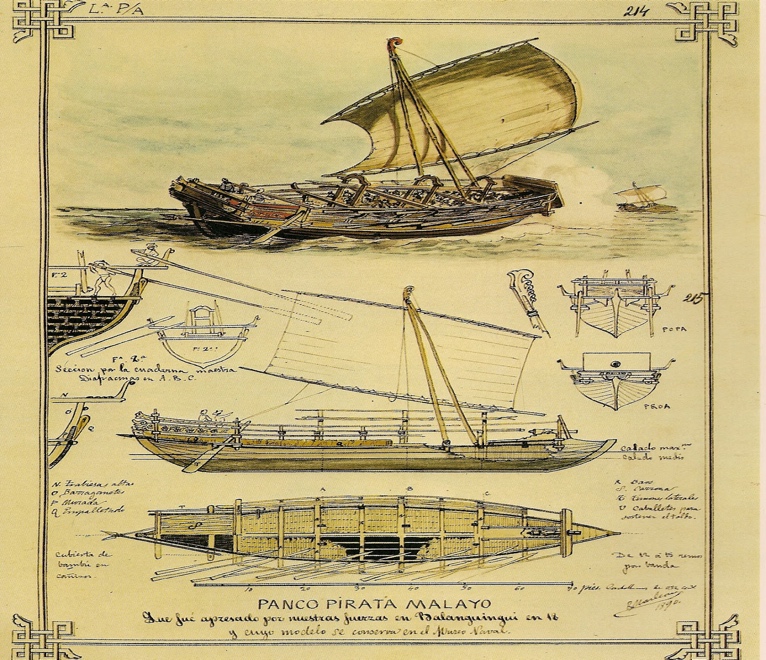

Garay warships of the Balanguingui Pirates, by artist Rafael Monleon. Photo credit: James Francis Warren (1985).

The Moro Pirates also maintained a fleet of PROAs (ancient cargo/fishing/warships) and more than 100 artillery pieces. Despite these advantages, the pirates were routed and defeated through strategy, tactics, good artillery, and naval gunfire support.

Lessons Learned:

VITAL USE OF INTELLIGENCE: The Spaniards made headway of the essence of intelligence by utilizing the locals on the particulars of the Forts to be assaulted, and developments on the fortifications and weapons inventory of the enemy.

NAVAL GUNFIRE SUPPORT: The Spanish Assault Force primary use of Naval Gunfire Support was of the essence in this naval operation as shelling contributed to surprise and sowing confusion to the enemy.

The Rio Grande De Mindanao Operation: Jan-March 1887

Almost 39 years after the successful amphibious assault of the Island of Balanguingi, a similar operation was launched by Spanish Forces on the Rio Grande De Mindanao in 1887.

Mindanao River as it was formally known was a river encompassing three Provinces –Bukidnon, Cotabato, and Maguindanao. It had seven tributaries. The Operation was part of the larger campaign against the Moros by the Spanish from the beginning of Spanish occupation until the sparks of the Philippine revolution.

The 1887 operation was led by Spanish General Julian Serina along with General Emilio Terrero, Col San Felin, and Col Matos with a force of 3,400 men, 120 Filipino militia known as Disciplinarios under Spanish Major Villabrille.

The objective was neutralizing the Moro Forts on the riverine coast and tributaries of the Rio Grande. The Spaniards employed both naval gunfire and local support. Moro response, on the other hand, were their lantakas and about 60 smaller canoes led by Datu Uto. On 10-March-1887, after 14 days of negotiations with emissaries, Datu Uto signed a Peace Accord along with his family and constituents.

The Moro force was effective in threatening smaller Spanish garrisons, but succumbed to overwhelming force, comprising the Spanish Army and Marines, Artillery Forces, and River Gunboats of the entire Spanish Naval Garrison in the Visayas region that were deployed. Arms coupled with a sound strategy are the lessons learned on this action.

About the Author:

CDR Mark R Condeno is Deputy Administrative Officer, Philippine Korean Friendship Center and Museum Curator, PEFTOK Korean War Memorial Hall Museum under the Dept of National Defense-Philippine Veterans Affairs Office. In 2007, he was Research Officer at the Office of the Naval Historian, PN; and Projects Officer at the Maritime Historical Branch of the Fleet-Marine Warfare Center, PN. He earned a BS Architecture at Palawan State University. In 1997, he completed the Basic Naval Reserve Officers Training Course, PN; and is with Bravo Class of 1999, PCG Auxiliary Officer’s Indoctrination Course. In 2002, he took the Aerospace Power Course at Air University, USAF. In 2008, he took the Military History Operations Course at U.S. Defense Technical Information Center. He is with Class 26 of the Executive Course on National Security at the National Defense College of the Philippines. He has been published in PAF Review, PAF Perspective, PN Journal, PN Digest, Rough Deck Log, CITEMAR6, USNI Proceedings, Asiaweek, USAF Air & Space Power Journal, and CIMSEC.