Southeast Asia straddles several of the most important maritime passageways in the world today. These arteries of global trade, transportation, and commerce are vital not only for regional but also global peace, security, and stability. Also, the region’s booming economies make it a bright spot for international investment. The waters in and around Southeast Asia are believed to hold substantial mineral, oil, and gas reserves. Moreover, it hosts some of the richest hotspots for marine biodiversity.

However, there are several challenges to regional security. The region’s porous maritime borders make it vulnerable to non-traditional security challenges, such as piracy, terrorism, human trafficking, and arms smuggling, to name a few. Also, large swathes of maritime Southeast Asia lie on the Pacific Ring of Fire, an area marked by increased seismic and volcanic activity. In addition to that, the area is beset by periodical typhoons, which cause direct and collateral damage to regional states. In addition, the congested maritime space of Southeast Asia presents a substantial navigation hazard to marine vessels.

In view of these security challenges, it is clear that no one country in Southeast Asia, using all its instruments of national power, can hope to address these challenges all by itself. The non-discriminatory, transnational, and shared nature of these maritime security threats necessitates a collaborative approach by regional states. ASEAN as the centre of a stable Southeast Asia serves as a venue where such a collaborative approach can be formulated.

In fact, ASEAN has just implemented its plan for economic integration, and we can expect that other pillars of ASEAN integration, such as the socio-cultural and politico-security environment integration, are to follow.

Moreover, ASEAN navies have just adopted the Standing Operating Procedures (SOP) on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) operations. With that in mind, ASEAN now has a viable framework for a collective response to these non-traditional security threats. The organization places great importance on respecting the diversity within itself and its individual member’s interests and sovereignty. This unique feature of ASEAN, among other regional blocs worldwide, may reflect itself in particular nuances that have to be observed in coalition operations.

Operational nuances in ASEAN HADR operations may manifest themselves in participating countries having different goals and interests, logistics, naval capabilities, training levels, equipment variety, doctrines, intelligence, leadership, and legal issues.

In terms of operational nuances, it is important for ASEAN to arrange the best command relationships with all participating navies to ensure mission success. ASEAN navies must also ensure they have sufficient resources for the tasks, as not to compete with the affected population. Further, ASEAN navies have different logistics systems. As such, regional commanders-in-chief can assume the role of interoperability advocates within the ASEAN bloc, focusing on the acquisition logistics process. Also, mechanisms that shall make technologically incompatible ASEAN partners interoperable should be devised. Financing HADR may present itself as a challenge to ASEAN navies. As such, ASEAN should design mechanisms to buy time for participating navies to discuss long-term financial arrangements, without affecting their operational tempo.

It is also clear that ASEAN navies possess different degrees and types of capability. Thus, sharing burdens equitably rather than equally can facilitate each participating navy to maximize their contribution to the overall HADR effort. In connection with that, ASEAN will have to be innovative to find effective roles for participating navies. Training levels have to be considered as well. It will do better for ASEAN navies to pursue joint HADR training to train up to a higher common standard, rather than ‘train down’ in making concessions to different competency levels between regional navies. These training exercises should involve all levels of command and include all staff, and rehearse operational tasks and orders, or new missions. Moreover, ASEAN navies’ training for HADR must revolve around some common doctrine and standards. The training must also be routinely assessed to ensure compliance to the common doctrine and standard. The ASEAN SOP on HADR can provide some of the functions of a common doctrine for future HADR exercises. Also, exercise planners should exploit equipment interoperability where it exists, and make allowances where it does not. Interoperability should stress more on correct processes and procedures, rather than technical compatibility.

ASEAN’s diversity also manifests itself in each member’s different military doctrines. ASEAN HADR naval planners should prepare for the peculiarities of each member states’ doctrines. This particular nuance requires understanding and adjusting for the differences involved. These differences can be managed through training exercises. Also, skilled liaison officers can be employed to smooth out doctrinal differences between ASEAN navies.

Regarding information sharing, planners should be sensitive of the historical and cultural differences of participating navies. Each ASEAN navy must have a clear delineation of information that may or may not be shared. ASEAN should also exploit any unique contribution of its member states, in order to accomplish the HADR mission at hand. Language can also present a challenge. Although English is the ASEAN working language, all member states have yet to achieve a working degree of proficiency. Aside from cultivating English language skills through student exchanges and local programs, ASEAN navies can also employ mobile learning devices and apps, such as smartphones, tablets, e-books, mp3 players, and so on.

ASEAN planners should keep in mind that a central norm of ASEAN is to respect each member state’s sovereignty. Moreover, each ASEAN navy has its own chain of command. While a unified chain of command akin to NATO is unlikely for ASEAN, planners should establish tasking that ensures unity of efforts. ASEAN too has to take into consideration legal prerequisites before engaging in HADR operations. It should look into whether its initiatives are valid based on international law, ASEANs own norms, each member states’ domestic laws, and the assisted state’s domestic law. It is recommended at all participating ASEAN navies in HADR operations have access to legal advice throughout the entire operation.

Cultural nuances encompass human factors such as religion, class and gender, discipline and cultural tolerance, work ethics, standards of living, and national traditions.

ASEANs religious diversity requires planners to be aware that each member state that religious requirements and sensitivities that must be considered in the planning of exercises or operations. Aside from religious differences, planners should also consider the interpersonal dynamics with each member states’ navy to ensure a harmonious working relationship. Gender roles and sensitivities, particularly on women, should be observed. Some ASEAN countries are more willing to commit more decisions, planning, and operations to women. However, other countries may have a more conservative view. Planners should also understand the different national traditions within ASEANs members, and have full cognizance of their implications to the conduct of coalition operations.

Despite several challenges to enhancing interoperability between ASEAN navies, the same non-traditional challenges open opportunities for a collective regional response to improve their HADR capabilities.

Southeast Asia’s maritime non-traditional threat environment presents challenges that no individual member can hope to solve alone. ASEAN, as the basis of a stable regional order and cooperation, is well-placed to be a venue for crafting solutions to these challenges. Using ASEAN as the foundation for regional cooperation, ASEAN navies can come up with an intra-bloc naval exercise for HADR capability building.

Building ASEAN navies’ competencies will take time. It entails confidence-building measures, fostering people-to-people ties, and sustained capability-building. It is high time for ASEAN navies to develop their HADR capabilities to ensure the continued prosperity of the bloc, and to secure its most valuable resource, its people. It is recommended that the ASEAN navies’ SOP on HADR should be promulgated in the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting to enshrine it as an official ASEAN policy. ASEAN should also pursue navy HADR exercises to operationalize the ASEAN navies’ SOP for HADR operations.

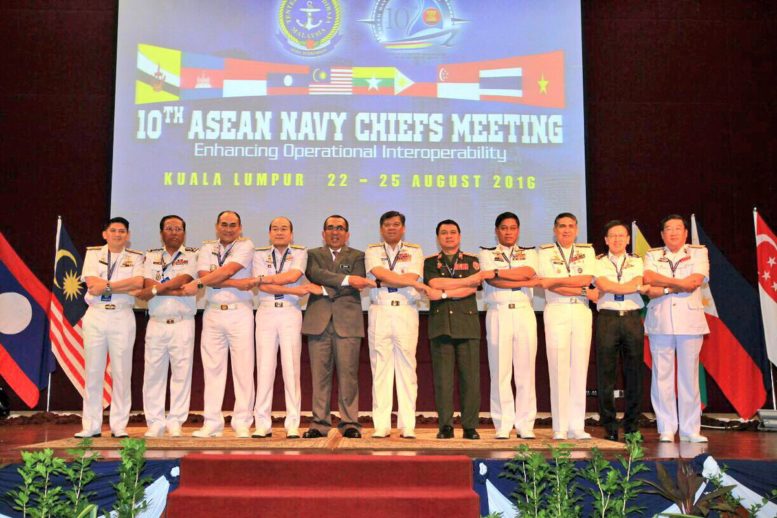

Co-written by SN2 Gabriel P Honrada PN, this speech was delivered by the Flag Officer-in-Command, Philippine Navy during the Viewpoint Exchange of the 10th ASEAN Navy Chiefs’ Meeting held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on 22-28 August 2016.