During the China-ASEAN Dialogue between Senior Defense Scholars held at Beijing, China on 11 – 15 March 2008, I presented a paper on Confidence-Building Measures Towards Greater Regional Stability. Military modernization in China was being perceived in a way that caused concern to some countries which fear a repeat of the arms race during the Cold War on one hand and smaller neighboring countries fearful of being bullied by its giant neighbor on the other, the need for confidence building measures within the region became that more urgent. China’s occupation of a few islets, starting a few years earlier, had become a destabilizing issue.

Since time immemorial, winning the trust and confidence of other countries, especially those nearby, has been universally practiced. In this era of globalization, cross-border issues and economic uncertainty, states seek better means to establish a “comfort zone” wherein they can conduct activities with one another, make collective decisions while, at the same time, pursue policies without jeopardizing their individual national interests. Confidence-building is a significant concern in the Asia Pacific, not only because of the great number of states in the region with some having historical enmities but, more importantly, because of the wide differences exhibited by states in approaching issues of common concern. For the region to be truly stable, therefore, a significant level of mutual trust has to be developed and ensured between and among regional actors.

The ultimate objective of confidence building is to achieve security from perceived threats. General and specific steps undertaken towards the minimization of apprehensions and distrust constitute what are formally called as confidence-building measures (CBMs). According to Sheldon W Simon, CBMs are arrangements “between two or more parties regarding exchanges of information and verification, typically with respect to the use of military forces and armaments.”

As an important element in defense and military affairs, CBMs spring from states’ inherent fear of unanticipated and miscalculated military attacks by other hostile or adversarial countries. They can be useful even at tactical level, as experienced in the use of the “communications hotline” (between commanders of maneuver forces) agreement, which prohibited preemptive attacks during the India-Pakistan hostilities in 1991. In a similar situation about a decade later, Indian and Pakistani commanders had the additional advantage of being personally acquainted by having attended together an advance security course sponsored by the Asia Pacific Center of Strategic Studies in Honolulu, as related to me by retired US Ambassador Charles Salmon (who was then in the APCSS faculty) during his visit in Manila in 2004.

However, the militarization of the South China Sea, including much of the West Philippine Sea, had seriously aggravated the situation. The Philippines’ going to the Arbitral Tribunal, moreover, had made the Philippines-China cleavage deeper.

Barely at the eve of the announcement of the Arbitral Tribunal’s decision to be made by July 12, 2016, I came across a series of papers written by Stewart Taggart in www.grenatec.com that suggests that joint development with China while risking joint patrol with the US may be a Philippine option.

In his July 9 article, Taggert surmised that:

In coming days, a UN Tribunal is expected to rule in the Philippines’ favor in its territorial dispute with China over Scarborough Shoal. China has flagged it will reject any tribunal decision that doesn’t go its way.

When that happens, the ball will be in the Philippines’ court. Manila’s newly-elected, largely-untested president Rodrigo Duterte will have important decisions to make.

Given Duterte’s ‘tough guy’ image, one response for Duterte could be to participate in joint patrols with the United States to Scarborough Shoal. That would be a stick, since China would almost certainly hesitate to directly antagonize a US escort ship.

A carrot, by contrast, would be an offer by the Philippines for joint oil and gas exploration of the Scarborough Shoal area. Duterte’s also lofted that trial balloon.

Taggert further justifies his proposal:

Chinese and Philippine companies have been holding on and off talks for years now regarding joint exploration and development of the Reed Bank area further south.

Some combination of the two would probably be Duterte’s best option. This would include a freedom of navigation exercise with US around Scarborough Shoal in response to the UN tribunal ruling, along with extension of a commercial olive branch to China of joint development at Scarborough Shoal.

Done right, neither side would lose face.

Both could potentially gain: China gets a social license, the Philippines gets needed capital –– and the Southeast Asian region would get a welcome template for managing rising military tensions.

The US — the Philippines’ primary military ally — would almost certainly bless this approach. It turns a territorial issue into a trade issue, providing breathing room for everyone. Result: nobody loses face; nobody starts shooting.

The US gets to claim a win on ‘freedom of navigation,’ the Philippines maintains its territorial assertion Scarborough Shoal lies within its 200 kilometer Exclusive Economic Zone, and China gets the best outcome for a bad hand of cards due to its miscalculated over-reach in the South China Sea.

For China, South China Sea territorial tensions with the neighbors is damaging China’s export infrastructure drive and the economic credibility of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Both are much more important right now than bullying the neighbors over offshore waters that may or may not have long-term economic value.

Taggart’s idea involves utilization of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which needs “international outlets for spare capacity in its infrastructure industry.”

Certainly it will easily gobble up spare capacity with just the gigantic project he has in mind: the resurrection by the Association of Southeast Asian Nation States of its Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGP) project, and its submission to China’s AIIB for funding.

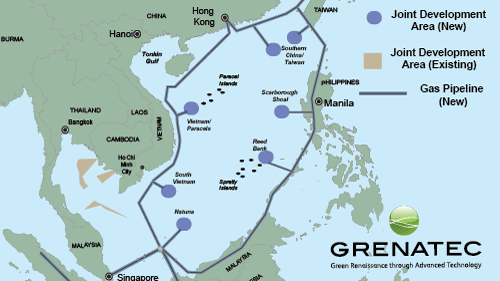

The proposal elevates the matter to regional rather than bilateral issue, which can be palatable to China only if the matter of ownership is not discussed. It will be acceptable to all ASEAN countries as they will share in the benefits of cheap energy (see map).

Regional confidence building is obviously more demanding and challenging than at the bilateral levels. Establishing regional CBMs would mean more parties to involve, more interests to satisfy, more threat perceptions to understand, more interpretations and assessments to explain, more strategies to incorporate, more proposals to consider, and more logistical concerns to address. Nevertheless, confidence-building measures at the regional stage also offer opportunities. An agreement forged at the regional level (especially if backed by sanctions for non-adherence) is harder to infringe. A country in violation of such an agreement faces the possibility of being multilaterally penalized (or at least criticized). Regional mechanisms, because of their geographical scope, can best cater to calls for regional stability.

Thus I fully subscribe to serious consideration by the National Security Council of the suggestions made by Stewart Taggart. The discussions on implementing the decision of the Arbitral Tribunal can be set aside formally and can be done separately at a convenient time acceptable to both China and the Philippines.