In August 2017, Chinese coast guard and navy ships were seen close by Sandy Cay, a sandbar neighboring Philippine-occupied Thitu (Pag-asa) Island in the South China Sea (SCS). Then Senior Associate Justice of the Philippine Supreme Court, Antonio Carpio, warned that Sandy Cay was “being seized (to put it mildly), or being invaded (to put it frankly) by China.” President Rodrigo Duterte and then-Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alan Peter Cayetano denied the allegation.

Four years later, Mr. Carpio, who is now retired, continues to claim that the Philippines has lost Sandy Cay to China. Philippine government officials also continue to reject Mr. Carpio’s claim.

The controversy persists to this day partly because neither side has presented conclusive evidence to the public. For its part, the Philippine government cannot simply disclose, for reasons of national security, intelligence on the situation on the ground or details of diplomatic discussions with other countries.

The controversy must be settled not only to set the record straight but also to determine whether the Philippine government should take further steps to defend Sandy Cay. Unfortunately, verifying either side’s claim would prove difficult. The place is remote, and publicly available information about the situation is scarce and sometimes conflicting. For instance, both sides, as well as independent sources, disagree even on basic facts about Sandy Cay’s geography, including its exact location in the South China Sea.

Still, publicly available sources —satellite imagery, government press releases, news reports, and expert analyses—can shed light on the situation in Sandy Cay if they are checked against each other. Relying on public evidence, this author finds that as of September 2021, the Philippines has not yet lost Sandy Cay to China. Before examining the evidence, though, this paper first clarifies where Sandy Cay is, and then explains why the Philippines should defend it.

Where Is Sandy Cay?

To begin with, basic facts about Sandy Cay’s geography must be clarified. There are three points of confusion.

First, some have doubted whether a sandbar named Sandy Cay exists at all and, if so, whether it is a high-tide feature —a formation that is above water at high tide, as opposed to a low-tide elevation, which is above water only at low tide, or a completely submerged feature.

In the South China Sea Arbitration, the Philippines argued that Sandy Cay no longer existed, but the tribunal disagreed. Sandbars, also known as sandbanks, sand cays, or sand keys, can be “dynamic”: they can “appear and disappear under the combined effects of astronomic tides, monsoon winds, and storms” and can change their location upon reappearance. “The absence of a sand cay at a particular point in time is thus not conclusive evidence of the absence of a high-tide feature,” the tribunal concluded. Sandy Cay, moreover, may no longer be dynamic and may have become permanent because of the debris from dredging in Chinese-occupied Subi (Zamora) Reef, about 10 nautical miles (19 km) southwest.

Second, some have mistaken Sandy Cay’s general location in the South China Sea. They have confused the sandbar with other features. Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque has mistaken Sandy Cay for Vietnamese-occupied Sand Cay (Bailan Island), which lies about 40 nautical miles (74 km) southeast of Sandy Cay. National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr. has also confused Sandy Cay with a sandy cay or a sand cay—generic terms for a sandbar.

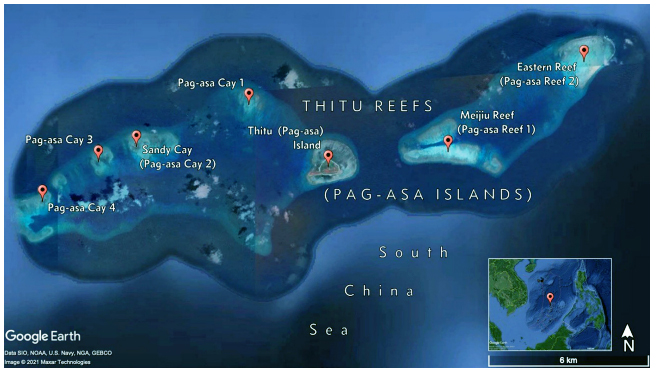

Sandy Cay is part of Thitu Reefs in the northwestern sector of the Spratly Islands. Thitu Reefs consist of two atolls. The eastern atoll comprises two reefs that are completely submerged. The western atoll comprises Thitu Island and several sandbars, one of which is Sandy Cay. Thitu Island and Sandy Cay are high-tide features. The other sandbars are either completely submerged features or low-tide elevations. Some may have also become high-tide features in recent years, but the available evidence is not yet conclusive.

Finally, some have mistaken Sandy Cay’s specific location within Thitu Reefs’ western atoll. Sandy Cay has been depicted as the sandbar closest to Thitu Island, to the northwest, or the one farthest, to the west-southwest. It has also been described as a set of four separate sandbars or a collection of three “coalescing” sandbars.

But the earliest known reference to Sandy Cay—HMS Rifleman’s fair chart from a hydrographic survey of Thitu Reefs in 1867 points to the sandbar lying about 4 nautical miles (7 km) directly west of Thitu Island. Filipino fishers and the Philippine government have also called that sandbar Sandy Cay. Precisely put, Sandy Cay lies at approximately 11°3′36′′ north latitude and 114°13′8′′ east longitude. Figure 1 shows its location within Thitu Reefs.

Sandy Cay is known by different names:

- In the Philippines, Sandy Cay is known as Pag-asa Cay 2. The name was given in August 2020, when the municipality of Kalayaan—the local government unit headquartered on Thitu Island that administers the Philippines’ Kalayaan Island Group claim in the Spratly Islands —renamed Thitu Reefs and the sandbars and reefs in the atolls. The national government adopted the new names on official nautical charts in September 2020. The Thitu Reefs are now known as Pag-asa Islands (not to be confused with Pag-asa Island, the Filipino name for Thitu Island).

- In China, Sandy Cay is known as Tiexianzhong Reef (Tiexianzhong Jiao 铁线中礁). Some sources also use the name Tiexian Reef (Tiexian Jiao 铁线礁), but strictly speaking, the name refers collectively to three sandbars in Thitu Reefs’ western atoll.

- In Vietnam, Sandy Cay is known as Hoai An Rock (Đá Hoài Ân).

Why Should the Philippines Defend Sandy Cay?

Sandy Cay is a sandbar that lies directly west of Thitu Island and stays above water at high tide. It is tiny, measuring no more than 240 m2, according to Google Earth satellite imagery captured in April 2019.

The sandbar’s tiny size makes it seem insignificant. Indeed, while responding to claims that China had seized Sandy Cay in August 2017, President Duterte asked, “Why should I defend a sandbar and kill the Filipinos because of a sandbar?” He also asked of China, “Why would they risk invading a sandbar and get into a quarrel with us?” But although Sandy Cay is tiny, from a legal perspective, its value is tremendous.

The 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea classifies a high-tide feature as either an “island” or a “rock.” An island can generate a territorial sea of up to 12 nautical miles (22 km), an exclusive economic zone of up to 200 nautical miles (370 km), and a continental shelf of up to 350 nautical miles (648 km) from the coast. A rock can generate only a territorial sea. Sandy Cay qualifies only as a rock because it is too small to “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own”—the main condition for a feature to qualify as an island.

Yet Sandy Cay’s status as a rock is significant for two reasons. First, the tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration found that no feature in the Spratly Islands is large enough to qualify as an island. The status of a rock, then, is the best status the feature could qualify for. Second, states may appropriate or assert sovereignty over a high-tide feature (i.e., an island or a rock) but not a low-tide elevation or a completely submerged feature. Sandy Cay is one of the few features in the Spratly Islands that are capable of appropriation.

Indeed, several states claim Sandy Cay. China and Taiwan assert sovereignty over Sandy Cay as part of their claims to all land features within their dashed-line demarcations in the South China Sea. The Philippines asserts the same as part of its claim to the Kalayaan Island Group in the Spratly Islands. Vietnam also asserts sovereignty over Sandy Cay as part of its claims to the entire Spratly Islands. These states are all legitimate claimants of Sandy Cay because the tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration did not—and could not—rule on questions of sovereignty over high-tide features in the South China Sea.

Sandy Cay itself, however, is less important than the territorial sea it can generate, which would engulf the Chinese-occupied Subi Reef and overlap with the territorial sea of Philippine-occupied Thitu Island.

Subi Reef is a low-tide elevation in its natural state even though China has transformed it into an artificial island. It is thus incapable of appropriation and cannot generate any maritime zone. Sandy Cay, by contrast, is a rock capable of appropriation and can generate a 12–nautical mile territorial sea. Because Subi Reef lies only about 10 nautical miles from Sandy Cay, Sandy Cay’s territorial sea would engulf Subi Reef.

If Sandy Cay did not exist or there were no high-tide features in Thitu Reefs’ western atoll, demonstrating sovereignty over Thitu Island would suffice to gain a claim to Subi Reef. The tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration explained: “Subi Reef would fall within the territorial sea of Thitu [Island] as extended by basepoints on the low-tide elevations of the reefs [sandbars] to the west of the island.”

But Sandy Cay does exist.

The Philippines, then, must demonstrate sovereignty over Sandy Cay to claim Subi Reef and extinguish any legal ground for China’s occupation and construction of an artificial island on the feature. Conversely, China must demonstrate sovereignty over Sandy Cay to bolster its claim to Subi Reef.

Additionally, the Philippines must demonstrate sovereignty over Sandy Cay to ensure that Thitu Island’s territorial sea would not shrink. If another state were sovereign over Sandy Cay, the territorial seas of Thitu Island and Sandy Cay would overlap because the features lie only about 4 nautical miles from each other. If the overlapping territorial seas were delimited along the median line, the area of Thitu Island’s territorial sea would shrink by about 40 percent.

Has the Philippines Lost Sandy Cay to China?

Sandy Cay is a valuable sandbar, which the Philippines cannot afford to lose. It was alarming when reports surfaced in August 2017 that Chinese ships had appeared close by and seemed poised to seize the feature. But Chinese Ambassador to the Philippines Zhao Jianhua assured President Duterte at that time that China was “not building anything” on the sandbar.

The incident was apparently resolved quickly. The following month, in September 2017, Ambassador Zhao declared, without elaborating, that the incident had been “successfully addressed through diplomatic channels.”

Then in November 2017, Philippine Secretary of National Defense Delfin Lorenzana revealed that the Philippines had in fact attempted to build fishers’ shelters on Sandy Cay earlier that year. China protested the attempt, and the Philippines withdrew its soldiers from the sandbar. No structure was built, but the attempt might have triggered China to launch patrols to Sandy Cay, leading to the sighting of Chinese ships near the sandbar in August 2017.

In April 2019, Philippine Ambassador to China Jose Santiago Sta. Romana also revealed that the Philippines and China had previously reached a “provisional agreement” to keep Sandy Cay unoccupied. This may have been the agreement reached by the two countries in September 2017.

Although the August 2017 incident has been declared “successfully addressed,” conflicting evidence has since surfaced. The controversy essentially covers three points: (1) whether the Philippines missed an opportunity to occupy Sandy Cay; (2) whether Chinese ships are loitering around the sandbar; and (3) whether Chinese ships have harassed Philippine vessels in the area. Overall, public evidence suggests that the Philippines has not yet lost Sandy Cay to China.

Did the Philippines Miss an Opportunity to Occupy Sandy Cay?

Those who say that the Philippines has lost Sandy Cay highlight a missed opportunity to assert sovereignty over the sandbar in 2017 when the Philippines backtracked from building fishers’ shelters after receiving a protest from China. There is no dispute that China has not physically occupied Sandy Cay. Indeed, there is no evidence of Chinese-built structures or stationed Chinese soldiers or agents on the sandbar. In August 2017, the US Department of Defense claimed that China had planted a flag on Sandy Cay, but it might have misunderstood reports from Philippine news media, which cited a sandbar near Loaita (Kota) Island, where China had allegedly planted a flag.

The Philippines, however, was likely correct to backtrack from the plan. The Chinese protest reportedly cited the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC). Paragraph 5 states that ASEAN countries and China should “exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from [the] action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features.” Although the DOC is not legally binding, the Philippines must not disregard it because doing so will reduce the country’s diplomatic leverage in championing compliance with the South China Sea Arbitration award.

Two ironies in the Chinese protest, however, must be noted. First, in 1994, China used the same pretense of building fishers’ shelters to occupy Mischief (Panganiban) Reef —a low-tide elevation that is legally part of the Philippine exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Second, when China began transforming its occupied features in the Spratly Islands into artificial islands in 2013, it had arguably disregarded the same provision of the DOC. China did not occupy any uninhabited feature, but it constructed artificial islands that now host the largest de facto military bases in the area. These artificial islands have undoubtedly “complicate[d] or escalate[d] [the] disputes and affect[ed] peace and stability.”

Are Chinese Ships Loitering around Sandy Cay?

Those who say that the Philippines has lost Sandy Cay imply that although the Philippines has honored the Chinese protest against the attempt to build fishers’ shelters on the Sandy Cay, China has rarely honored Philippine protests against the presence of Chinese ships around the sandbar. National Security Adviser Esperon, however, has mentioned that although China has not completely withdrawn from Sandy Cay, it has occasionally reduced the number of Chinese ships in the area in response to Philippine protests.

States normally do not publicize every diplomatic protest they make, so it would prove difficult to confirm whether a decrease in the number of Chinese ships around Sandy Cay correlates with the filling of a Philippine protest. Nonetheless, the number of Chinese ships in the area does fluctuate. Still, it is rarely zero. Indeed, both sides acknowledge that although China has not occupied the sandbar itself, it has maintained a presence in the surrounding waters.

Media reports, government releases, and satellite imagery demonstrate that Chinese ships have loitered in Thitu Reefs, including around Sandy Cay, since August 2017. These ships appear to be large fishing boats, but they are often Chinese maritime militia vessels in disguise and are sometimes accompanied by Chinese coast guard and naval ships in a layered formation. Navy helicopters have also reportedly flown over the sandbar.

Initially, Chinese ships seemed to visit Thitu Reefs only occasionally and in small numbers. But starting in December 2018, the deployments became more frequent and larger in size, sometimes reaching numbers of nearly 100 a day. This apparent “swarming” of Chinese ships into Thitu Reefs prompted the Philippines to publicly denounce China in April 2019 —a break from the usual quiet diplomacy on SCS matters.

Despite objections from the Philippines, China has refused to completely withdraw its ships from Thitu Reefs. Reports and satellite imagery throughout 2020 show that Chinese ships have mostly stayed in the area. This year, the Philippine government publicly acknowledged the ongoing challenge posed by these Chinese ships. In a protest against China in May 2021, the Philippines deplored the “incessant deployment, prolonged presence, and illegal activities of Chinese maritime assets and fishing vessels in the vicinity of the Pag-asa Islands [Thitu Reefs].” Satellite imagery in August 2021 shows 18 ships stationed in Thitu Reefs.

Analysts have claimed that the loitering of Chinese ships in Thitu Reefs is connected to the Philippines’ infrastructure upgrades on Thitu Island. Chinese ships, then, may not completely withdraw from the area while upgrades are underway. Construction began in mid-2018. A sheltered port and a beaching ramp were completed last year, while repairs to the island’s runway are set to start this year.

In March this year, however, the Philippines began to push back against the presence of Chinese ships, not only in Thitu Reefs but also within the Philippine EEZ in the South China Sea. The pushback followed the discovery of around 220 Chinese ships anchored in Whitsun (Julian Felipe) Reef that month. In response, the Philippines increased its patrols in the South China Sea, including in Thitu Reefs.

Have China’s Ships Harassed Our Vessels near Sandy Cay?

Those who say that the Philippines has lost Sandy Cay to China point out that Chinese ships have blocked Philippine government vessels and fishing boats from going near the sandbar. Philippine government officials deny such harassment but acknowledge that Chinese ships have been monitoring the activities of Filipino fishers from Thitu Island.

Public evidence is mixed regarding whether Chinese ships have harassed Philippine vessels.

In August 2017, a former member of the House of Representatives, Gary Alejano, citing sources from the Philippine military, claimed that Chinese ships had prevented a vessel of the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources from going near one of the sandbars west of Thitu Island. He also alleged in February 2018 that Chinese ships had closed in on a Philippine Navy vessel in the area. In March 2019, Kalayaan Mayor Roberto del Mundo acknowledged that Chinese ships would approach Philippine fishing boats trying to go near any of the sandbars.

In May 2019, however, a survey ship of the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority went to the sandbars and successfully collected hydrographic data without being blocked by any Chinese ship. Moreover, in June 2020, local fishers told journalists visiting Thitu Island that “things ha[d] become better” and that Chinese ships would no longer block their paths to the sandbars. The visiting journalists also went ashore on a sandbar without any problem, although a China Coast Guard vessel later appeared close by.

But in January 2021, it seemed that things had again gone worse. A video taken by a local fisher from Thitu Island at that time shows several Chinese ships getting in his way during an attempt to go to one of the sandbars. The fisher retreated and returned to Thitu Island.

In March 2021, however, the Philippine government increased its patrols in the SCS. Since then, Philippine military and law enforcement vessels have toured Thitu Reefs more frequently, and thus far, no report has emerged of Chinese ships interfering in a patrol. In contrast, during a patrol around Scarborough Shoal (Bajo de Masinloc) in April 2021, Philippine Coast Guard vessels were dangerously approached by China Coast Guard ships. The Philippines later protested the incident.

Overall, the mixed evidence does not show a persistent pattern of obstruction of Philippine vessels by Chinese ships, unlike in Scarborough Shoal. But it also shows that harassment has occurred previously and may occur again sporadically.

Obstruction by Chinese ships seems to be more apparent with Philippine fishing boats. Yet, Philippine government officials have denied that such obstruction amounts to harassment. But according to Mayor Del Mundo, Filipino fishers would withdraw their boats when encountering Chinese ships to avoid confrontation. Thus, there may be no harassment because Philippine fishing boats would retreat before getting near enough to be actually harassed by Chinese ships.

In other words, the case does not seem to be that Filipinos cannot fish near Sandy Cay, but that they would rather not do so out of fear for their personal security. Filipino fishers have reason to be fearful: Chinese ships not only dwarf Philippine fishing boats, but they have also previously sunk Philippine and Vietnamese fishing boats in the South China Sea.

Worse, the government has given conflicting guidance to Filipino fishers on Thitu Island. In March 2019, the Department of National Defense said that the military has been encouraging Filipino fishers to fish around Sandy Cay. The department added that Filipino fishers “ha[d] not been fishing in the vicinity of the sandbar, even before the Chinese fishing vessels were sighted in the area.” But in June 2020, fishers in Thitu Island told journalists that the military had discouraged them from fishing in the area. In defense, Secretary Lorenzana said that the fishers could fish in other areas. Mayor Del Mundo also discouraged his constituents from fishing around Sandy Cay in January 2021.

In May 2021, the National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea, the agency charged with coordinating Philippine policy on South China Sea matters, encouraged Filipino fishers to fish again around Sandy Cay.

Fortunately, the Philippine government recently increased patrols around Sandy Cay, though Filipino fishers may take time before they could regain the courage to fish again in the area.

Conclusion

The Philippine government disputes the claim that China has seized Sandy Cay, but the controversy relates only to what constitutes “seizure.” Everyone agrees that no physical occupation of the sandbar has occurred. But everyone also agrees that Chinese ships —fishing, maritime militia, coast guard, and navy— have loitered in the surrounding waters since August 2017.

The Philippine government also disputes the claim that Chinese ships have harassed Philippine law enforcement and fishing vessels going to Sandy Cay, but the controversy relates only to what constitutes “harassment.” There is no dispute that Chinese ships monitor the activities of Philippine vessels near Sandy Cay. But there is also no dispute that the Philippines has increased its patrols around Sandy Cay since March 2021.

Amid these points of controversy, the public evidence suggests that the Philippines has not yet lost Sandy Cay to China. Filipino fishers could still fish near Sandy Cay without being regularly blocked by Chinese ships. Similarly, the Philippine military and law enforcement agencies could still patrol the surrounding waters without being regularly chased by Chinese ships. China, however, is clearly watchful of developments in the area.

The Philippine government must strive to preserve the status quo and, where possible, revert to the situation prior to 2017 or at least improve the current situation. Sandy Cay must remain unoccupied, and Chinese ships must not prevent Philippine fishing boats and government vessels from going near it.

At the very least, the Philippine government must maintain the momentum of the increased patrols around Sandy Cay. The patrols should have three goals. First, they should restore Filipino fishers’ courage to fish around Sandy Cay. Second, they should signal to China that the Philippines, too, is watchful of developments in the area. Finally, they should deter fishers —Filipino, Chinese, Taiwanese, or Vietnamese— from engaging in unsustainable fishing around Sandy Cay, where the marine environment has already been deteriorating.

The situation in Sandy Cay has indeed deteriorated since August 2017, but there is still room for improvement. Sandy Cay, after all, is not yet lost.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the assistance of Jeremy Dexter B. Mirasol in the conceptualization of an early draft of this paper.

About the Author:

Edcel John A. Ibarra (edcel.ibarra@gmail.com) is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. The views expressed in this publication are of the author alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs, or the Government of the Philippines. This article was originally published in FSI Insights vol. 7, no. 2 (November 2021), at https://fsi.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FSI-Insights-November-2021.pdf