The right of innocent passage refers to the right of foreign vessels to freely navigate in the territorial sea of another State without conducting activities that prejudice said State’s interests.1 2 It is akin to an easement or servitude whereby one has a right in relation to another’s property. Innocent passage through the territorial sea of a State over which it has sovereignty is not to be deemed a violation of the dominion or sovereignty of said State over said maritime space; the recognition of such right in favour of foreign vessels is made in the interest of navigation.

The ‘Battle of the Books’ – Mare Liberum and Mare Clausum and the right of passage

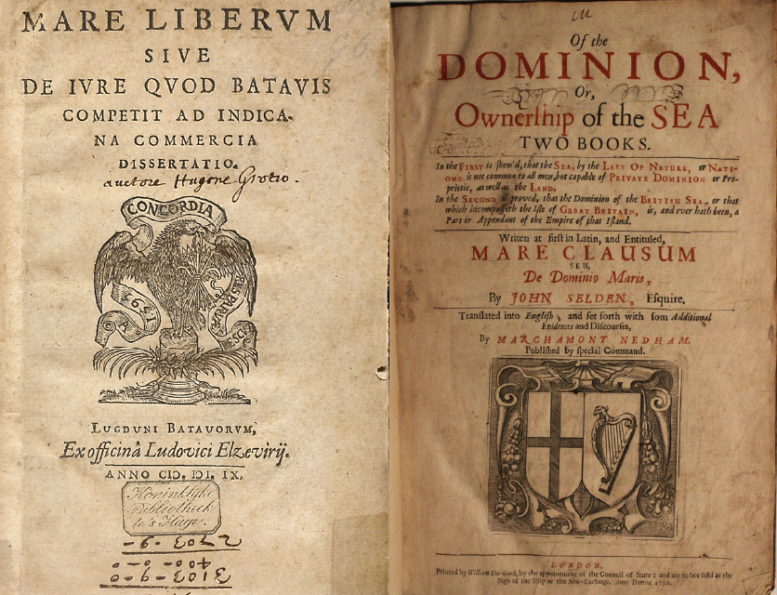

Certainly, if anyone is to talk about the law of the sea, a reference to the great ‘Battle of the Books’3 is indispensable. As a consequence of the division of the world between Spain and Portugal by Pope Alexander VI, the Dutch East India Company requested the Dutch scholar and lawyer Hugo Grotius to publish in 1609 (or 1608) Mare Liberum (Mare Liberum sive de iure quod Batauis competit ad Indicana commercia or Freedom of the Seas or the Right which belongs to the Dutch to take part in the East Indian trade.) Such treatise was to ‘refute the unjustified claims of Spain and Portugal to the high seas and to exclude foreigners therefrom.’4 Thus, in opposition to claims of ownership over the seas by Spain, Portugal and even England, the Hollander Grotius argued that the seas – their vastness rendered them indivisible and the resources of which were inexhaustible – were free for all and could not be subject to the control of any ruler.

This concept of free seas did not pass unopposed – other thinkers including the English John Selden espoused the idea that ‘the sea, by the law of nature or nations, is not common to all men, but capable of private dominion or property as well as the land; that the King of Great Britain is lord of the sea flowing about, as an inseparable and perpetual appendant of the British Empire.’5 In response to Grotius’ Mare Liberum, Selden published Mare Clausum (Mare clausum seu de dominio maris or Of the dominion or ownership of the sea).

In Chapter II of Mare Clausum, Selden took note of the concern over the impairment of the law of commerce and travel (law of nature) on the freedom of commerce, passage and travel, if ownership of the seas was permitted. Thus, in Chapter XX entitled An Answer to the objection, concerning Freedom of Passage to Merchants, Strangers and Sea-men, he explained that ‘the offices of humanity require that entertainment be given to strangers, and that inoffensive passage be not denied them’. He continued to explain that in allowing such passage, the dominion of the thing is unaffected – ‘But what is this to the dominion of that thing, through which both merchants and strangers are to pass? Such a freedom of passage would no more derogate from it. […]’

As early as the 17th century, and even to an advocate of ownership of the sea, the idea of passage through such owned seas had been recognised in the interest of commerce. The following century, in his treatise on international law, the Law of Nations, Monsieur Emerich de Vattel would acknowledge this concept of free passage through the coastal waters pertaining to a nation thus:

These parts of the sea, thus subject to a nation, are comprehended in her territory; nor must any one navigate them without her consent. But, vessels that are not liable to suspicion, she cannot, without a breach of duty, refuse permission to approach for harmless purposes, since it is a duty incumbent on every proprietor to allow to strangers a free passage, even by land, when it may be done without damage or danger.

Right of innocent passage in the territorial sea under the modern law of the sea

In the codification attempts of international law, the centuries-old idea of innocent passage through the territorial sea would be accepted as a limitation to the sovereignty of the coastal State over said waters. At the 1930 Hague Conference for the Codification of International Law, together with the agreement on the sovereignty of the coastal State over its territorial sea, ‘the right of innocent passage of foreign ships through [said sea] was generally recognised because of the importance of the freedom of navigation.’6 This concept would be codified in the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, and later in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC) thus:

Subject to this Convention, ships of all States, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea.7

Indeed, the right of innocent passage is a firmly established rule of international law.

Warships and the Right of Innocent Passage

Whilst there is no express provision in this regard in the LOSC, it is understood that foreign warships likewise enjoy the right of innocent passage. This idea is inferable from other related provisions of the LOSC, particularly Subsection A, Section 3 of Part II that reads ‘Rules Applicable to All Ships’ (underscoring supplied), Art 19(2) that lists activities that include those normally performed by warships and Art 20 on submarines which are generally military vessels.8

Further, subsequent to the adoption of the text of the LOSC in 1982 and to settle their flip-flopping positions on the matter, the United States of America (USA) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) jointly issued in Wyoming, USA in September 1989 the Uniform Interpretation of Rules of International Law governing Innocent Passage. Paragraph 2 of said rules expressly mentions warships as likewise having the right of innocent passage thus:

2. All ships, including warships, regardless of cargo, armament or means of propulsion, enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea in accordance with international law, for which neither prior notification nor authorization is required. (Underscoring supplied)

It is important to note that the foregoing notwithstanding, State practice in regard to the exercise of the right of innocent passage for warships has neither been uniform nor consistent. In a fairly recent publication9, a list is made of some 40 States, including the Republic of the Philippines10, that require prior authorisation, notice, notification or permission in relation to a foreign warship’s right of innocent passage.

Conclusion

The right of innocent passage is universally recognised in international law in the interest of navigation; this right exists for both merchant ships and warships. Inoffensive passage – to borrow the words of the English John Selden – should not be restrained as it does not in any way impair the sovereignty of the coastal State. The nuances between the exercise of the right of innocent passage of merchant ships and that of warships do not however appear to have been fully expressed in the conventional rules of the LOSC. Indeed, State practice assumes great importance in this discourse.

About the Author

Atty. Yano is an Associate at the Del Rosario & Del Rosario Law Offices, a member of the Institute of Maritime and Ocean Affairs and presently the Vice-President for Special Projects of the Maritime Law Association of the Philippines. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any organisation or his affiliations.

Sources

- Passage in waters not covered by State sovereignty is passage simpiciter and not the exercise of the right of innocent passage but of freedom of navigation.

- The right of innocent passage is likewise exercisable in archipelagic waters and certain straits used for international navigation.

- First use of the term is attributed to Professor Nys

- Introductory Note of James Brown Scott to The Freedom of the Seas (1916)

- Ibid.

- Yoshifumi Tanaka, The International Law of the Sea, Second Edition, p. 20

- Art 17, LOSC

- Tanaka, p. 91

- J. Ashley Roach and Robert W. Smith, Excessive Maritime Claims, Third Edition, pp. 250-251

- See note 109 to Innocent Passage of Warships International Law and the Practice of East Asian Littoral States, published in the Asia-Pacific Journal of Ocean Law and Policy in 2016; this requirement was expressed in the aide-mémoire of 23 September 1968 from the Department of Foreign Affairs to the British Embassy. Therein the Philippine State communicated that ‘[…] the […] combined units of British and Australian armed public vessels, or any other armed foreign public vessel for that matter, cannot assert or exercise the so-called right of innocent passage through the Philippine territorial sea without the permission of the Philippine Government.’