The sea referred to as the ‘West Philippine Sea’ comprises different maritime zones, not all of which actually pertain to the Philippines as its territory from the perspective of international law. Given that the Philippines is a member of the international community, it is only advisable that it employ an approach consistent with international law in respect of its territory and maritime spaces.

AO 29 s 2012

Under Administrative Order 29 series of 2012, all the maritime areas on the western side of the Philippine archipelago as enclosed by the archipelagic baselines drawn in accordance with Republic Act 9522 are referred to as the ‘West Philippine Sea.’ To claim however that all these areas are subject to Philippine territorial sovereignty or are part of Philippine territory will be inaccurate under international law, particularly the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC) to which the Philippines is a party. A zonal approach to the ‘West Philippine Sea’ is essential; thus, one will be more conscious and cognizant of the different maritime zones composing the West Philippine Sea as well as the functions each of them serves.

The Maritime Zones composing the ‘West Philippine Sea’

Territorial Sea of the Archipelago. From the archipelagic baselines up to 12 nautical miles (nm) seaward is the territorial sea of the Philippine archipelago. Over the territorial sea – the seabed and subsoil, the water column and the superjacent airspace – the Philippines has sovereignty exercisable subject to international obligations. (An example of this obligation is the right of innocent passage available to foreign ships through the Philippine territorial sea.) Beyond this 12nm territorial sea, however, is no longer an area of Philippine sovereignty.

Exclusive Economic Zone of the Archipelago. Beyond the 12nm territorial sea up to 200nm seaward is the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) established through Presidential Decree 1599 series of 1978. Whilst the EEZ is encompassed by the nomenclature ‘West Philippine Sea,’ it does not mean that it is Philippine national or territorial waters. To be sure, the Philippines no longer has sovereignty over said area. Rather, it has sovereign rights over the natural resources therein; put simply, exclusive economic rights. Thus, under international law, whilst the Philippines does not own its EEZ, the economic uses, e.g., fishing, in such maritime space including the superjacent airspace are exclusive to the Philippines; no other state can undertake economic activities therein without the consent of the Philippine state. Given that it is not Philippine territory, other states may however enjoy non-economic uses in the area, such as freedom of navigation as well as the right of overflight.

Continental Shelf of the Archipelago. Just like the EEZ, the continental shelf is another distinct zone where the Philippines has sovereign rights – not sovereignty – existing ipso facto and ab initio. It is also not properly deemed part of Philippine territory. It is nonetheless important to further distinguish the EEZ from the continental shelf. For one, the continental shelf regime pertains to the seabed and subsoil – not to the waters – beyond the 12nm territorial sea. Thus, as a rule, fish are supposedly not discussed in relation to the continental shelf. Such natural resources as oil, gas and minerals are the resources that are properly discussed in relation to the continental shelf regime. Further, whilst the EEZ is only up to 200nm, the continental shelf may extend up to 350nm. Thus, on the eastern side of the archipelago, the Philippines successfully established the outer limits of the continental shelf in the area referred to as Benham Rise. It is important to remember however that maritime entitlements beyond 200nm are covered by the continental shelf regime alone, not the EEZ. Stated otherwise, the waters above the outer (or extended) continental shelf, i.e., beyond the 200nm EEZ, are already part of the high seas beyond the exclusive control of the Philippines. Owing to the division between the EEZ and the continental shelf, these two may co-exist only up to 200nm measured from the Philippine archipelagic baselines; beyond 200nm only sovereign rights in respect of the latter are possible.

No Contiguous Zone. Another maritime zone recognized in international law is the contiguous zone. If claimed, it grants onto the relevant coastal state limited law-enforcement authority even beyond the 12nm territorial sea up to 24nm measured from the relevant coast. Contrary to common understanding, the Philippines does not have a contiguous zone for the reason that it has not (yet) claimed such zone.

The Territorial Sea of Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal). As we know from the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration case, Bajo de Masinloc was found to be a high-tide elevation –specifically a rock per Article 121(3) of the LOSC – lying at 116.2nm from Luzon. Whilst Bajo de Masinloc is located within the 200nm EEZ or continental shelf; it is neither a part of the EEZ nor of the continental shelf. Being a high-tide elevation and thus a piece of territory in itself, it has its own personality so to speak; in fact, it generates its own maritime zone. Being a rock, however, it generates no more than a territorial sea up to 12nm; it does not have an entitlement to continental shelf rights or EEZ rights. Given its location, the waters beyond the 12nm territorial sea of Scarborough Shoal form part of the 200nm EEZ of the Philippine archipelago; the seabed and subsoil beyond its 12nm territorial sea form part of the continental shelf of the Philippine archipelago.

Bajo de Masinloc. Photo Credit: Oceandots.com | NASA

The Territorial Seas of the Kalayaan Islands

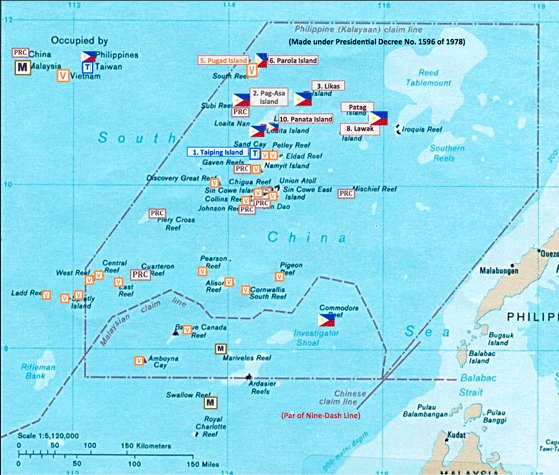

Anent the Kalayaan Islands, the arbitral tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration case found that none of the high-tide features there is a fully-entitled island capable of generating an EEZ or continental shelf. In other words, at best, the high-tide features forming part of the Municipality of Kalayaan could only generate their respective territorial seas up to 12nm – just like Bajo de Masinloc. Similarly then, the waters beyond the 12nm territorial sea of said features, but within the 200nm zone measured from the archipelago, will be part of the EEZ of the archipelago; the seabed and subsoil beyond the 12nm territorial sea form part of the continental shelf of the archipelago. Some of the high-tide features composing the Municipality of Kalayaan lie beyond 200nm from the archipelago though. Thus, the waters beyond the territorial sea generated by such features are no longer part of the EEZ generated by the archipelago.

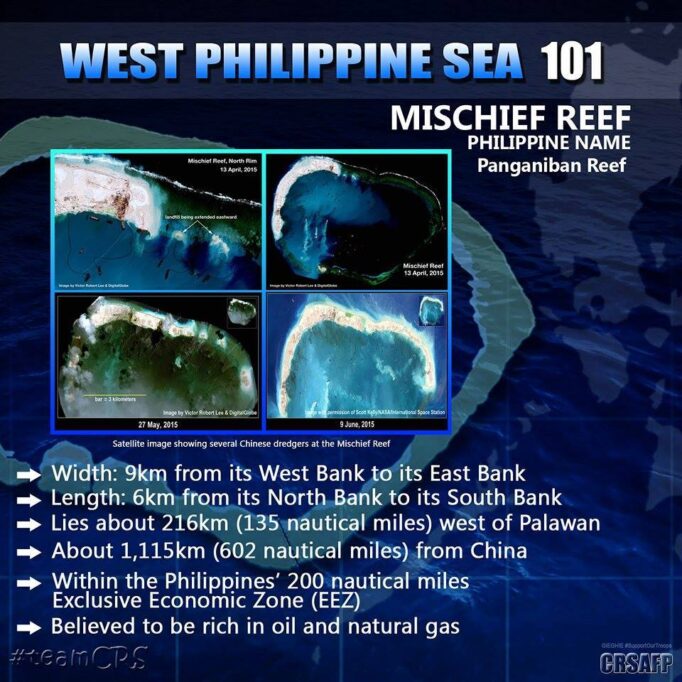

Panganiban Reef (Mischief Reef). Photo credit: CRSSFP

Panganiban (Mischief) Reef and Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal as Low-tide Elevations

Panganiban Reef and Ayungin Shoal are low-tide elevations located within 200nm from the archipelagic baselines of the archipelago. Unlike high-tide elevations, these low-tide elevations are merely part of the seabed specifically, the 200nm continental shelf given their location. As discussed, it is not part of Philippine territory under international law. However, the Philippines has sovereign rights – but not sovereignty – over these features.

Ayungin Shoal

The Maritime Zones of Sabah

Sabah is another component of Philippine territory which generates a territorial sea, an EEZ and continental shelf that merge with those of the archipelago.

Some Observations on the ‘West Philippine Sea’

Contrary to the understanding of some if not many, the EEZ is not sovereign waters; the high seas freedom of navigation, among others, is therefore also available to foreign vessels in the Philippines’ EEZ. Thus, the mere presence of foreign vessels in the Philippines’ EEZ is permissible. Of course, if such presence is for purposes other than what said foreign vessels can legitimately carry out in the EEZ, it is a different thing altogether and is objectionable.

Another common misconception is that the waters surrounding Bajo de Masinloc and (some of) the Kalayaan Islands simply form part of the EEZ. This interpretation fails to take into account the fact that these high-tide elevations also generate their respective territorial seas that which should be given effect. What form part of EEZ waters are those waters beyond said territorial seas, provided that they be within the 200nm zone measured from the archipelago.

Further, despite being called an ‘island,’ it must be understood that Pag-asa Island is legally a rock per Article 121(3) of the LOSC as found by the arbitral tribunal in the SCS Arbitration case. Thus, it has its own territorial sea, but nothing more. It should also be recalled that Pag-asa Island lies at 227.4nm from the archipelago; hence, already beyond the 200nm EEZ.

To claim that Panganiban Reef and Ayungin Shoal are territories of the Philippines will run afoul of international law. As discussed above, they are merely low-tide elevations forming part of the seabed or the continental shelf of the archipelago. And under international law, the continental shelf is beyond the claim of territory by a state. Certainly, Philippine sovereign rights – not sovereignty – over these features must be protected. To be sure, the construction of an artificial island over Panganiban Reef without the consent of the Philippines is violative of such rights.

Really and truly, the term ‘Kalayaan Island Group’ can now be confusing – hence, the use of the term ‘Kalayaan Islands’ above instead – such that it is (still) thought that all the marine areas enclosed by the coordinates indicated in Presidential Decree 1596 series of 1978 are Philippine sovereign or national waters. As discussed above, Philippine sovereign waters in the Municipality of Kalayaan are limited to the territorial seas around each of the high-tide features.

Conclusion

A zonal approach to the West Philippine Sea leads one to be mindful of the fact that different maritime zones actually compose what is referred to as the ‘West Philippine Sea.’ Thus, one becomes conscious about the extent (consequently, the limits) of the Philippine claim of maritime territory in relation to the ‘West Philippine Sea.’ Indeed, unless the commonly-held idea that the ‘West Philippine Sea’ is entirely Philippine territory is rectified, the (legal) issues surrounding it cannot be properly appreciated.

The ‘West Philippine Sea’ is not entirely Philippine sovereign waters. In fact, most of the area encompassed by the ‘West Philippine Sea’ is the EEZ (and continental shelf). Whilst the Philippines has sovereign rights in the EEZ (and continental shelf), it can neither claim nor treat this as its national waters without offending international law. Indeed, sufficiently understanding the nature of Philippine interests in the ‘West Philippine Sea’ is essential to effectively protecting and defending such interests.