The Philippines is endowed with thousands of beautiful beaches. Except for the Cordilleras, there are beach destinations in all regions. Coastal attractions can be found from the northernmost islands of Batanes to the southernmost parts of Tawi-Tawi.

The Philippines is one of the favorites of foreign tourists, and beaches still remain as their top destination. Statistics show that the lion’s share of foreign tourists to the Philippines come from cold climate countries and regions such as China, Europe, North America and South Korea. Most of these foreigners visit the beaches than other parts of the country.

The University of Cambridge report Climate Change: Implications for Tourism stated that “Coastal tourism is the largest component of the global tourism industry, with more than 60% of Europeans opting for beach holidays, and the segment accounting for more than 80% of US tourism revenues.”

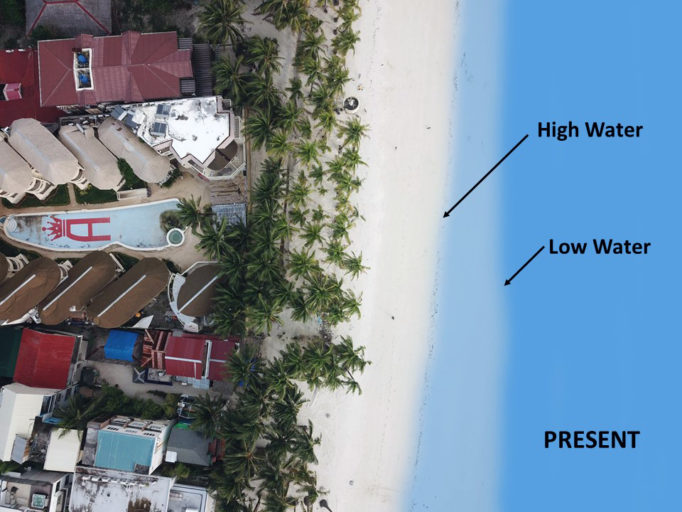

While beaches attract more tourists than other places, they are also more vulnerable to degradation because they are easier subjected to erosion or submersion. Submersion can happen if the level of the sea rises. When sea level rises (SLR), the beach becomes narrower as shown in the comparison in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Current sea level

Figure 2. Level of water surface after the sea level rise. Note. The beach area becomes narrower because part of the original beach has submerged.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report 2014 Synthesis Report projected that the sea level rise in 2046 may go as high as 0.38 meter and in 2100 may go as high 0.82 meters. With that amount of SLR, will there be Philippine beaches that will be submerged?

Figure 3. High water and low water lines of Boracay.

Note: The darker blue shows the low water and the lighter blue shows the high water.

Figure 4. High water and low water lines after SLR.

Figures 3 and 4 show the comparison of the high and low water lines in a portion of Boracay before and after SLR.

Beaches recede as the sea level rises but the slopes in the coasts will also vary. Thus, the amount of beach erosion is not constant. Long coasts with high elevation may still maintain a fairly wide area of beach after sea level rise. However, the coasts with low elevation might have narrower area of beach after sea level rise.

In the case of Boracay Island, there is a no build zone twenty-five (25) meters from the edge of the mean high-water mark measured inland and a setback distance of 5 meters from nearest edge of the structure. Structures are already allowed with some limitations beyond this 30-meter easement.

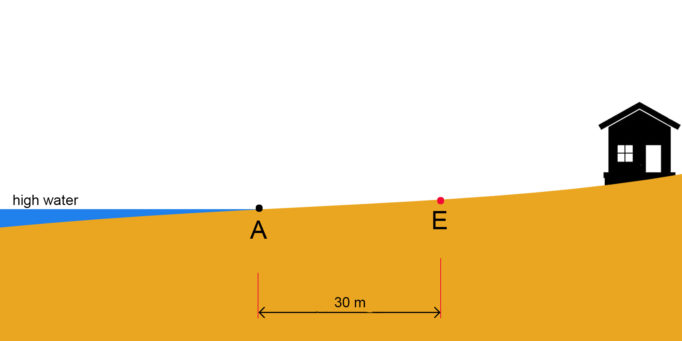

Figure 5. High water and the no build zone. Note: Point A is the location of the high water and Point E is the 25+5 easement.

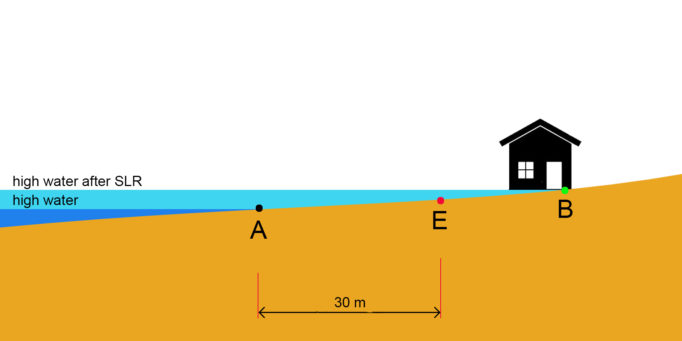

Figure 6. High water before and after SLR. Note: Point B is the location of high water after SLR.

Figure 5 shows the 30-meter (25 + 5) distance from the high water where no structures can be built in Boracay. Figure 6 shows the situation after the SLR.

Figure 6 shows that even if the structure is built more than 30 meters from the existing mean high water line, it will be submerged if the location of the structure is below the high water after the SLR. The susceptibility of a point to submersion is not dependent on its distance from the high water line but on its elevation above the water. Thus, the 25 + 5 no build zone is only effective in maintaining a wide beach area if the outermost edge of the no build zone is above the high water after the SLR.

Foreign studies have shown that degraded beaches lessen the desirability of tourist spots. In Philippines, there is no sufficient study conducted on the location and number of beaches affected by SLR. However, if sea level rise happens, the impact is very high considering the billions of incomes generated from the beach destinations. The question is whether tourists would still flock to our coastal attractions like Boracay if the beaches will be narrow.

The Municipality of Malay, Aklan which covers the Boracay Island is ahead of other coastal municipalities for implementing a 25 + 5 easement thru their Municipal Ordinance No. 2000-131. However, not all coastal municipalities have similar ordinance. In many tourist spots, structures are already constructed near the high water lines without taking into consideration the effect of SLR.

Currently, pollution is the immediate concern of the Philippine Government as seen in its action in Boracay. SLR is not yet a major issue for beach tourism since it is slow. Although the rate of SLR is not abrupt, the effect is permanent. Unlike pollution, it is not reversible and cannot be solved by rehabilitation.

Boracay alone has attracted millions of foreign tourists. Considering there are hundreds of beach destinations, the Philippines attracts hundreds of thousands of foreigners. Boracay and many other coastal areas consider tourism as their lifeblood. What would happen if the white beaches of these destinations disappear because of SLR?

In South Korea, the most visited beach is Haeundae Beach located in Busan. The beach is roughly 1.5 km long with a 30-meter wide sand. Just like Boracay, people flock to Haeundae Beach every summer.

The Travel Weekly Asia (2017) reported that Busan is estimated to have drawn more than 10 million domestic visitors and 2 million international tourists in 2016, pulling in a combined 4.1 trillion won (US$3.6 billion) in tourism revenue.

Between 1990 and 2013, a total of 53,000 cubic meters of sand has been dumped in the Haeundae beach, equal to 13,000 loads by an eight-ton truck.

If the beaches in the Philippines be subjected to submersion, is the government willing to spend millions, just like what the Korean Government did in Haeundae, to maintain the attractiveness of the beaches and sustain the income generated from tourists?

CONCLUSION

We should learn from the Korean experience and tackle the problems before they get worse. After addressing the pollution in Boracay, it might be high time that the Government also review the existing laws on easements in coastal areas. Coastal municipalities should review their ordinances on no-build zones and consider SLR in the drafting their provisions. No-build zones should not only be measured horizontally from the high water but the slope of the coast must also be taken into account.

About the Author. Commander Carter Luma-ang is currently the Chief of the Maritime Affairs Division of the Hydrography Branch of the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA). He earned his Master in National Security Administration from the National Defense College of the Philippines (RC-51).