French industrialist Henry Fayol, recognized by many as father of modern management and author of the book titled “Industrial and General Administration” published in 1916, identified 14 Principles of Management that serve as guidelines for managers to perform their duties and responsibilities. One of these principles is “unity of command.” Simply put, this principle means that subordinates must have, and receive orders from, only one superior.

Fayol posited that unity of command prevents dual subordination, avoids overlapping orders and instructions, enhances efficiency, and maintains discipline. His proposition is supported by many thinkers and practitioners in public administration and business management like Marshall and Gladys Dimock, John Pfiffer, Robert Presthus, William Fox, Ivan Meyer, Luther Gulick and Lyndall Urwick.

But some management writers, like Frederick Taylor, Herbert Simon, Seckler-Hudson and J.D. Millet, argue against unity of command. They contend that this principle goes against the specialization principle and dual supervision of technical/operational and administrative. Luther Gulick countered these arguments saying, “Any rigid adherence to the principle of unity of command may have it absurdities. But they are unimportant in comparison to the certainty of confusion, inefficiency and irresponsibility which arise from the violation of the principle.” Gulick also reechoed a biblical lesson: “A man cannot serve two masters.”

While the unity of command principle applies to nearly all types of human organizations the military is at the forefront. It is one of the principles of war and continues to remain valid.

Half a century earlier, before Fayol’s famous book came out, General Ulysses Grant, General-in-Chief of the Union Army, unified “all northern military efforts under one brain” to defeat the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. General Grant’s war exploits influenced succeeding U.S. military officers who fought in World War 1 like General John Pershing, then Col. Leslie McNair who later earned the accolade of “Brain of the Army” and then Lt. Col. George Marshall, later a leading military figure during World War 2 and defense secretary after the war.

Unlike in the American Civil War where military commanders gave orders and directives to subordinates under the same flag, the challenge of directing forces from different nations by a single commander was extremely difficult. During WW1 the Supreme War Council designated French General Ferdinand Foch as General-in-Chief, Western Front, with direct command over assigned French, British and American forces. General Pershing, commander of the U.S. Expeditionary Forces, resisted the piecemeal engagement of his forces and demanded that American forces retain their national identity under his overall command. He asked the American liaison officer, Colonel Bentley Mott, to communicate his concerns to Foch’s combined force headquarters. After presenting Pershing’s concerns, French General Foch quietly told American Colonel Mott: “I am the leader of an orchestra. Here are the English Bassos, here are the American baritones, and there the French tenors. When I raise my baton, every man must play, or else he must not come to my concert.”

General Pershing had fully understood General Foch’s view of unity of command as he believed that without a supreme commander there would not be a unity of action. Nonetheless, he continued to be irritated by the way the Supreme Commander fielded the multinational forces. Colonel George Marshall, Pershing’s operations chief, keenly observed the resistance of his commander but was convinced that the unity of command principle must prevail over personal differences.

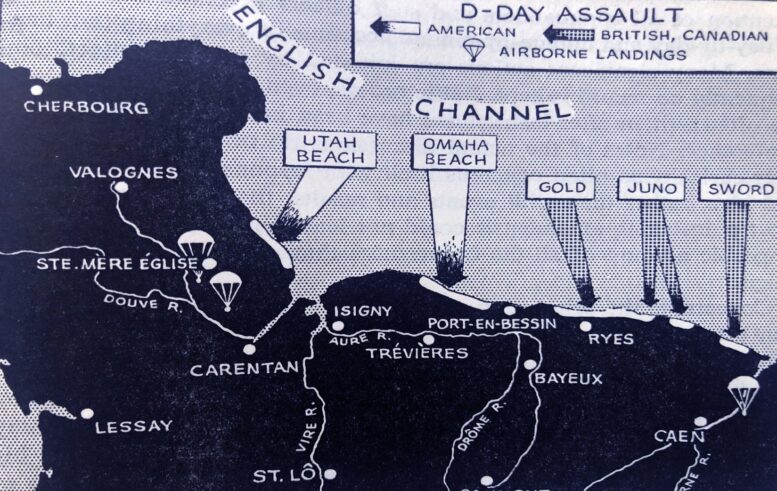

General Marshall’s experience in WW1 led him to introduce the unity of command principle under civil authority in Washington DC when he became U.S. Army Chief of Staff in 1939. The war in Europe started months after his assumption but the U.S. did not declare war on Germany until December 1941. In January 1942, the U.S. and Britain agreed to create a Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS), a cooperative military arrangement, along the lines of the British committee system that included strategy formulation and management. The CCS reported both to U.S. President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill. Both Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations, and General Marshall became members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff along with their British counterparts who were represented in the U.S. by permanently stationed senior officers. General Marshall’s superb inter-personal relationship convinced Roosevelt and Churchill that General Dwight Eisenhower was the right military commander to spearhead the liberation of Europe starting with cross channel invasion and subsequent inland offensive operations.

After WW2, the U.S. formally adopted the Unified Command Plan and organized the unified, or combatant, commands. But service rivalry persisted. The Joint Chiefs of Staff was directly above the unified commands. It took years to address some nuances associated with the structure but when clear and smooth command relationships were established “the result was an enduring moral singleness and unity of purpose.” The basic considerations of the Plan were military unity under single geographical commander and a workable strategy crafted by a civilian-military team. Forty years later the command relationship changed with the enactment of the Nichols-Goldwaters Act of 1986. This law relegated to the background the authority of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and put the Defense Secretary as the immediate supervising authority of the unified commands.

In smaller scale, the application of the principle of the unity of command can be described by the actions of French naval commanders during WW2. When Germany attacked France, many troops and naval ships influenced by General Charles De Gaulle sailed to Britain and established a Free France government to continue German resistance. In contrast, after the defeat of French forces in Metropolitan France the new head of government, Marshal Philippe Pétain, signed a Franco-German armistice. In June 1940, that divided the country into two zones: a German-occupied portion and the other a German-controlled “corporate state” called Vichy France where the French could exercise nominal “sovereignty.” French colonies with military and naval units remained loyal to the Vichy government. As a result, even the British and American governments were in a conundrum about which French regime had more credence, the fascist Vichy regime of the beloved elderly Philippe Pétain that 90% of the French supported because of its refusal to join the Axis, or the arrogant and courageous French Resistance advocate Charles de Gaulle who lead the government-in-exile French Françaises Libres to join the Allied Forces and fight against the Axis powers.

But those doubts ended in July 1940 when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the re-appointed First Lord of the Admiralty, launched Operation Catapult to seize, neutralize and destroy all elements of the French Navy under Pétain’s Vichy government. De Gaulle directed the commanders of Free France naval forces to follow the operational concept of “autonomy and collaboration” when fighting with the British. One of his naval commanders, Vice Admiral René Émile Godfroy, who was tasked to operate alongside the British forces under Admiral Andrew Cunningham in Alexandria, Egypt, believed “that effective operations should be conducted under a single commander” and decided to be subordinated to the Royal Navy. The British-led naval operation in Alexandria was a success. This local initiative of Godfroy, though, was not sanctioned by his superiors.

While the complexity of applying the principle of unity of command becomes higher when dealing with large multinational coalitions and alliances, the benefits of the principle’s foundations remain: better performance, maintenance of discipline, avoidance of dual command, and prevention of confused situations. Grant, Foch, Marshall and Godfroy are examples of military leaders who demonstrated how the principle of unity of command worked to accomplish their missions and objectives.

Finally, Dwight Eisenhower’s words on this principle may be tweaked to guide and inspire Philippine civilian government or military or uniformed service officers working in inter-agency task forces: “Alliances in the past have often done no more than to name the common foe, and the unity of command has been a pious aspiration thinly disguising the national jealousies, ambitions, and recriminations of high ranking officers, unwilling to subordinate themselves or their forces to a command of different service… I was determined, from the first, to do all in my power to make this a truly Allied Force, with real unity of command and centralization of administrative responsibility.”